Bench press vs. flys: which is better for the pecs? [Study review]

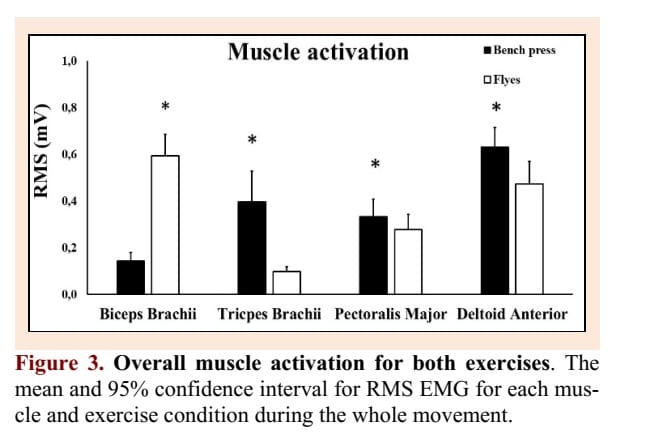

The bench press beat flys in terms of average muscle activation for all target muscle groups, including the pecs: see the data below.

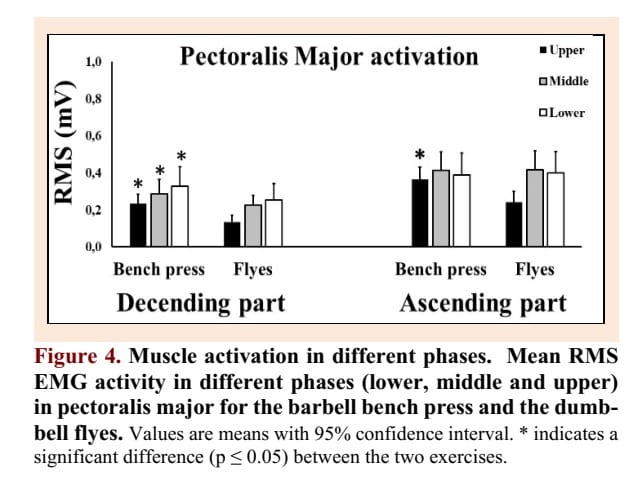

So case closed: flys are useless, presses are better for everything? No, that’s not how we should interpret EMG data. The difference in muscle activity came mostly from the top third of the movement, where the bench press still effectively trained the pecs but flys did not: see the data below. This makes perfect biomechanical sense of course: with dumbbells the external moment arm, which is the horizontal length of your literal arm in this case, is maximal in the bottom position, so you get a great stretch, but there is virtually no tension on the pecs in the top position, as there’s no external moment arm for horizontal shoulder flexion/adduction anymore then. Basically, bench presses train the pecs over a greater effective range of motion (ROM). Most research finds training with greater ROM stimulates greater muscle growth. That’s likely due to 2 reasons, but only 1 is relevant here.

Many people would probably argue flys also lose out on constant tension and thereby metabolic stress. I don’t think that’s relevant, as most research has debunked metabolic stress as an independent driver of muscle growth.

So should we do dumbbell flys? I basically never use them with my clients. Instead, you get the best of all worlds, as well as lower injury risk, with a properly set up cable fly: I call these Bayesian flys and you can read exactly how and why you should do them in this article.

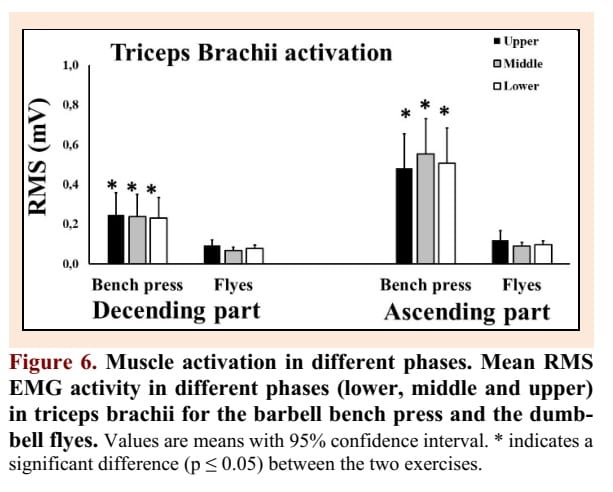

Another interesting finding of this study was the pattern of triceps activity. Many powerlifters argue that the triceps is mostly active in the top position. That’s why block presses are commonly prescribed to build the triceps. I think this is misguided for 2 reasons.

First, as I’ve previously showed, it’s simply not true that the triceps is that much more active in the top of the movement: see the data below. Triceps activity is relatively constant during a bench press. There’s no biomechanical rationale as to why it would be much higher at the top.

Second, bench presses of any kind are not great triceps builders in the first place. I previously posted a review of how most studies find bench presses don’t build the triceps nearly as well as the pecs. While many people thought this was circumstantial evidence, as it didn’t compare the growth rate vs. another exercise, recent research has validated it: bench presses don’t effectively stimulate the long head of the triceps, whereas triceps extensions do. The long head is a biarticulate muscle: it aids not just in elbow extension but also shoulder extension. During a bench press, maximally contracting the long head would cause a significant shoulder extension moment. Since the shoulder flexion moment is likely more limiting than the elbow extension moment during a bench press, this means full contraction of the long head of the triceps is often not desirable.

Reference

Tom Erik Solstad, Vidar Andersen, Matthew Shaw, Erlend Mogstad Hoel, Andreas Vonheim, Atle Hole Saeterbakken. (2020) A Comparison of Muscle Activation between Barbell Bench Press and Dumbbell Flyes in Resistance-Trained Males. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine (19), 645 – 651.