Are artificial sweeteners bad for your gut bacteria?

In 2014 a study by Suez et al. caused massive uproar about the safety of artificial sweeteners, specifically their effects on gut health. The researchers concluded that consuming artificial sweeteners disrupts our gut microbiome and causes metabolic disease, particularly glucose intolerance.

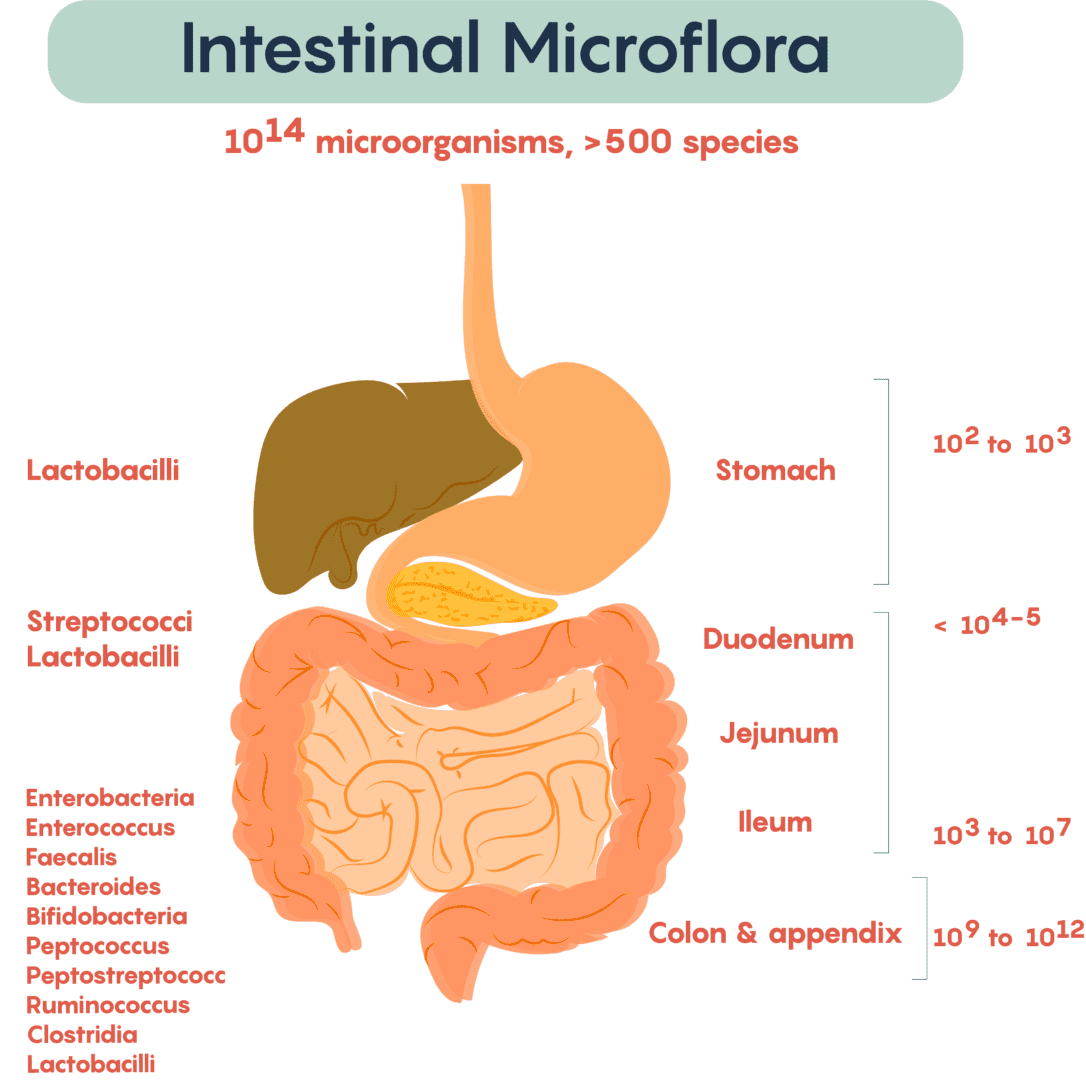

Our digestive tract (gut), especially our large intestine (colon), is populated by a staggering number of micro-organisms, including over a thousand bacterial species. Together, our gut microbiome has as many cells as our own body and over a 100 times more genes. Are low-calorie sweeteners killing the little friends in our colon? Source

The one study to alarm them all

The study by Suez et al. was published in Nature, arguably the most prestigious journal in the world. They’re renowned for only accepting high-quality publications. However, this study had major limitations and raised a huge controversy.

First, most of this study was done on mice. Rodents have a very different metabolism than humans. Extrapolating dosages is particularly difficult. There were only 2 analyses on humans.

The first human analysis was observational only. They correlated sweetener usage with multiple markers of diabetes in a different ongoing study. People that used more sweeteners also had higher rates of glucose intolerance. However, they were also fatter. Fatter people always have more symptoms of metabolic syndrome, regardless of sweetener usage, so there’s no surprise here. A later study published in Nature showed that fatter people often use more artificial sweeteners in an attempt to lose weight. So correlations between sweetener usage, bodyweight and metabolic disease are entirely to be expected and are not evidence that sweeteners cause metabolic disease. Rather, it may just be that overweight individuals are more likely to use sweeteners and more likely to have metabolic diseases.

The researchers do state glucose exposure (A1C) remained significantly different when adjusted for BMI between high users and non-users of sweeteners, but they don’t say how they selected these comparison groups or give any more details about this analysis. The Methods section in general is very brief and lacking in details.

To determine if the relation between sweetener consumption and metabolic disease was causal or just a co-occurrence, they conducted a controlled experiment. Well, that’s putting it favorably. They had 7 subjects who didn’t consume artificial sweeteners consume the equivalent of 5.6 cans of Cola Tab every day for a week. After that week, 4 out of those 7 people showed poorer glycemic responses and altered gut microbiota.

In the other 3 ‘non-responders’ as the researchers called them, the average glycemic response actually improved, albeit non-significantly. That begs the question: did the average glycemic response of the 7 people worsen significantly? The researchers don’t show this. There was also no control group to compare the change to.

Even if the group average increased significantly and the 4 subjects weren’t simply outliers (or consuming something else: their diets weren’t controlled), is suddenly going from zero to ~6 cans of Cola Tab a day for a week representative of long-term health effects?

We know the human gut can majorly adapt to a wide variety of diets and initial adaptations are not always reflective of long-term changes. For example, one year-long study found that both low carb and low fat diets cause significant changes in people’s gut microbiome in the first 3 months, but “after these initial shifts, the microbiota returned near its original baseline state for the remainder of the intervention, despite participants maintaining their diet and weight loss for the entire study.”

Say we take the results from this research at face-value. This still doesn’t justify the researchers to talk about sweeteners – plural – because the subjects only consumed commercial saccharin. So these findings needn’t apply to any other sweeteners.

Moreover, commercial saccharin is 95% glucose. This amounted to only about 7 grams of glucose per day by my calculations, but that’s still an increase in pure-sugar energy intake not accounted for that could have influenced the study.

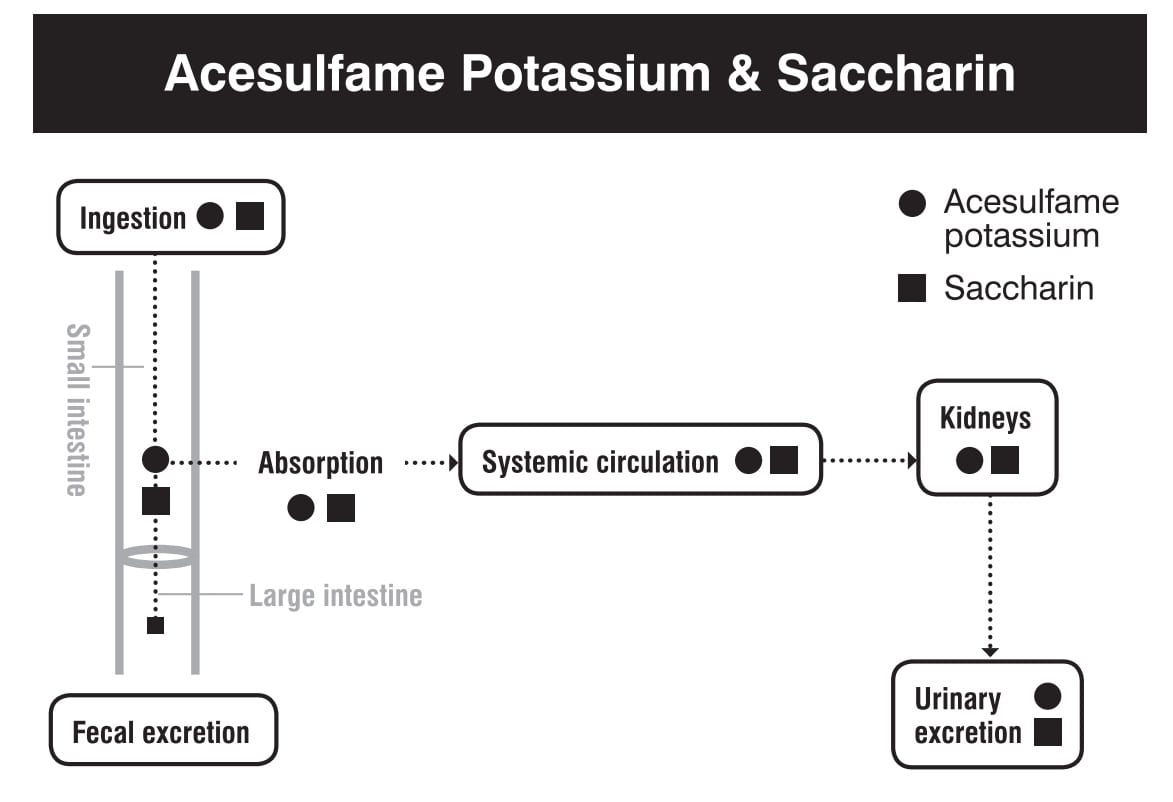

In terms of mechanism, it’s somewhat hard to see how saccharin would harm our gut, because saccharin is not digested or metabolized in the human body. Most saccharin is absorbed and excreted unchanged by the kidneys in our urine before it even reaches the large intestine where most of our microbiota reside. The remainder just passes through us without digestion, out via our feces, so it can’t serve as fuel for any bacteria.

Saccharin passes through our body unchanged (as does acesulfame potassium, another sweetener). Source

In contrast to Suez et al.’s dubious correlation and 7-subject uncontrolled pilot study, a multitude of randomized controlled trials since the 1920s have found that pure saccharin consumption has no effects on blood sugar or insulin levels and is very safe even for diabetics up until the acceptable daily intake (ADI), which is 5 mg/kg/d as set by the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA).

It’s hard to consume more than the acceptable daily intake of saccharin, because saccharin is not commonly used anymore due to its bitter, metallic aftertaste. So the results of the Suez et al. study are somewhat moot to begin with. Let’s look at the more popular low-calorie sweeteners stevia, sucralose and aspartame.

Does aspartame influence your gut bacteria?

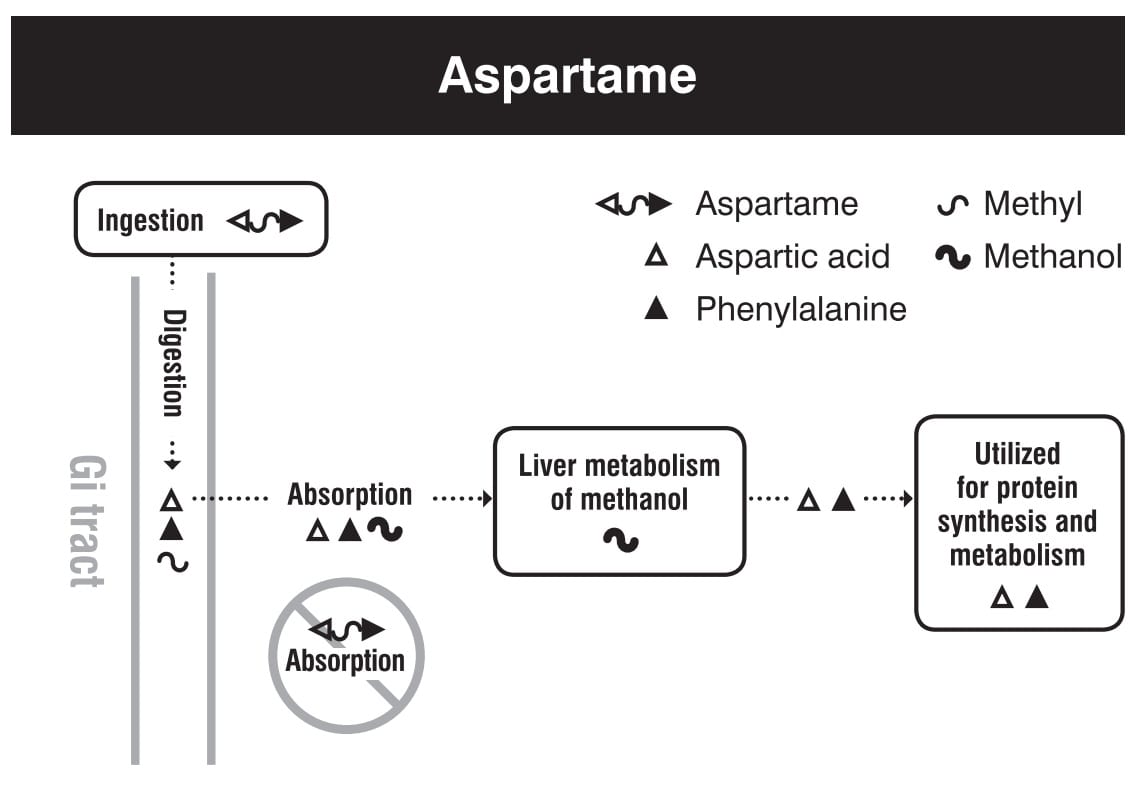

Aspartame is an artificial sweetener found in many diet sodas. Even though it’s produced synthetically, aspartame consists of entirely natural compounds: phenylalanine with an added methyl group and aspartic acid. These are natural amino acids that are also found in our bodies and in many foods. As a result, aspartame is digested just like dietary protein. It’s rapidly broken down to its constituent amino acids and absorbed. Nothing reaches the large colon where most of our microbiota reside and no aspartame enters our blood or organs even at very high doses. It’s thus hard to imagine how aspartame could harm our gut health. Indeed, a 2020 Canadian randomized controlled trial found no effect of aspartame consumption on the gut microbiota.

The ADI for aspartame as set by the JECFA is 40 mg/kg/d. To reach the maximum intake that’s still almost certainly safe, an 80 kg person (176 lb) needs to consume 80 x 40 / 37 = 86 packets of Equal sweetener. ADIs have a 100-fold error margin, so to reach a level of consumption that has actually been found to cause harm in animals or humans, you have to consume a whole lot of aspartame.

Aspartame is fully and harmlessly broken down into natural protein metabolites before being absorbed, just like protein from food. Source

Sucralose sweeteners and the effect on gut bacteria

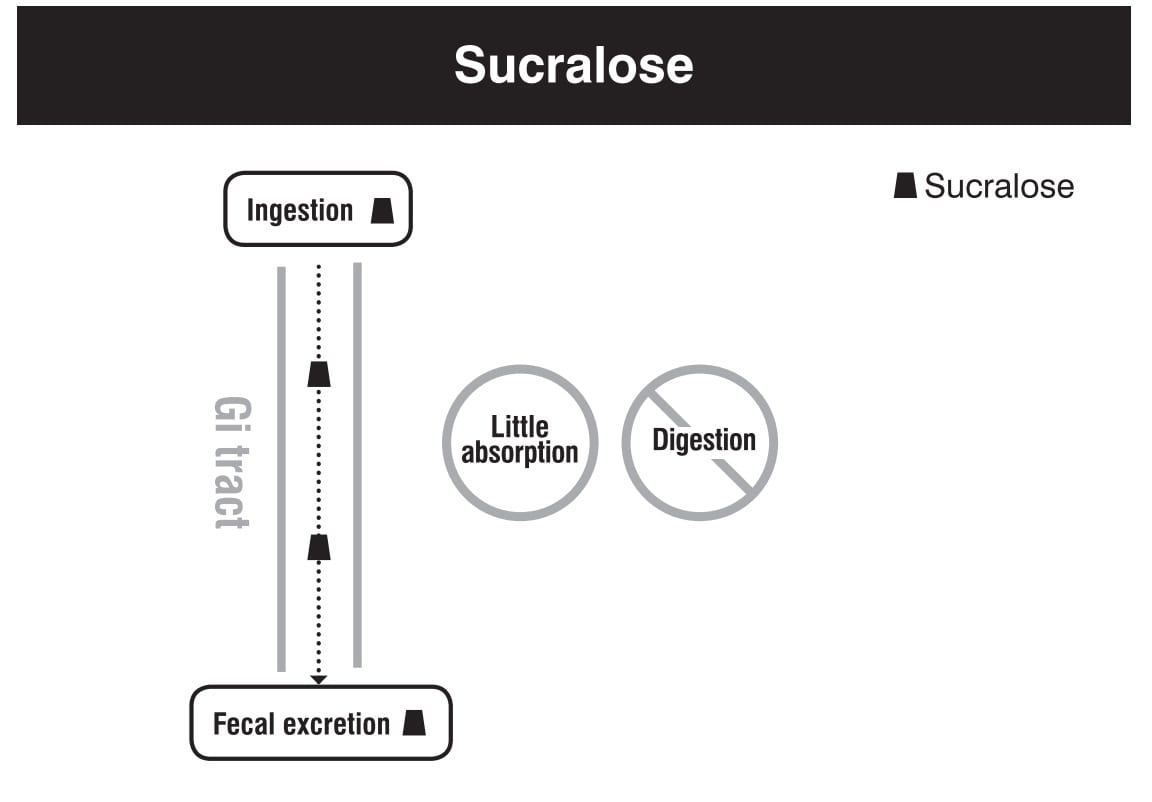

Sucralose, most commonly known in the form of the brand Splenda, is another artificial sweetener that’s not far off from a natural compound. It’s produced synthetically, but sucralose is merely a modified form of table sugar (sucrose), also called tri-chloro-sucrose. This modification makes sucrose unavailable to human glycosidic enzymes, so it cannot affect our blood sugar or be metabolized for energy.

In fact, the human body can’t do much with sucralose at all. We can barely digest, absorb or metabolize sucralose. Most sucralose just passes through us, out via our feces. The small part that’s absorbed is excreted via our kidneys, out into our urine, without being digested. Only about 2% of sucralose is metabolized into minor metabolites and this occurs in the body, not in the gut.

Nevertheless, several rodent studies have shown changes in some bacterial concentrations in our gut in response to high dose sucralose vs. water consumption. Most of these studies did not control for the dietary intake of the rats and had no proper control group. More importantly, these changes were not accompanied with any adverse effects. Almost any dietary change results in a change in bacterial concentrations in our gut. This doesn’t mean there’s any harm. In fact, an abundance of randomized controlled trials in humans support the safety of sucralose consumption at least up until the ADI.

Of note, Thomson et al. (2019) performed a replication of the infamous Suez et al. (2014) study in Nature, this time with more subjects and a control group, and their conclusion was clear: “consumption of high doses of sucralose for 7 days does not alter glycaemic control, insulin resistance, or gut microbiome in healthy individuals.” In 2020, a Canadian randomized controlled trial again found no effect of sucralose consumption on the gut microbiota in human subjects.

The ADI set by the JECFA is 15 mg/kg/d. There are 12 mg sucralose in a packet of Splenda, so if you weigh 80 kg (176 lb), you can safely consume at least a 100 packets of Splenda per day.

Most sucralose we consume just passes through us and goes straight out via our feces. None is digested. Source

Most sucralose we consume just passes through us and goes straight out via our feces. None is digested. Source

The effects of Stevia on gut bacteria

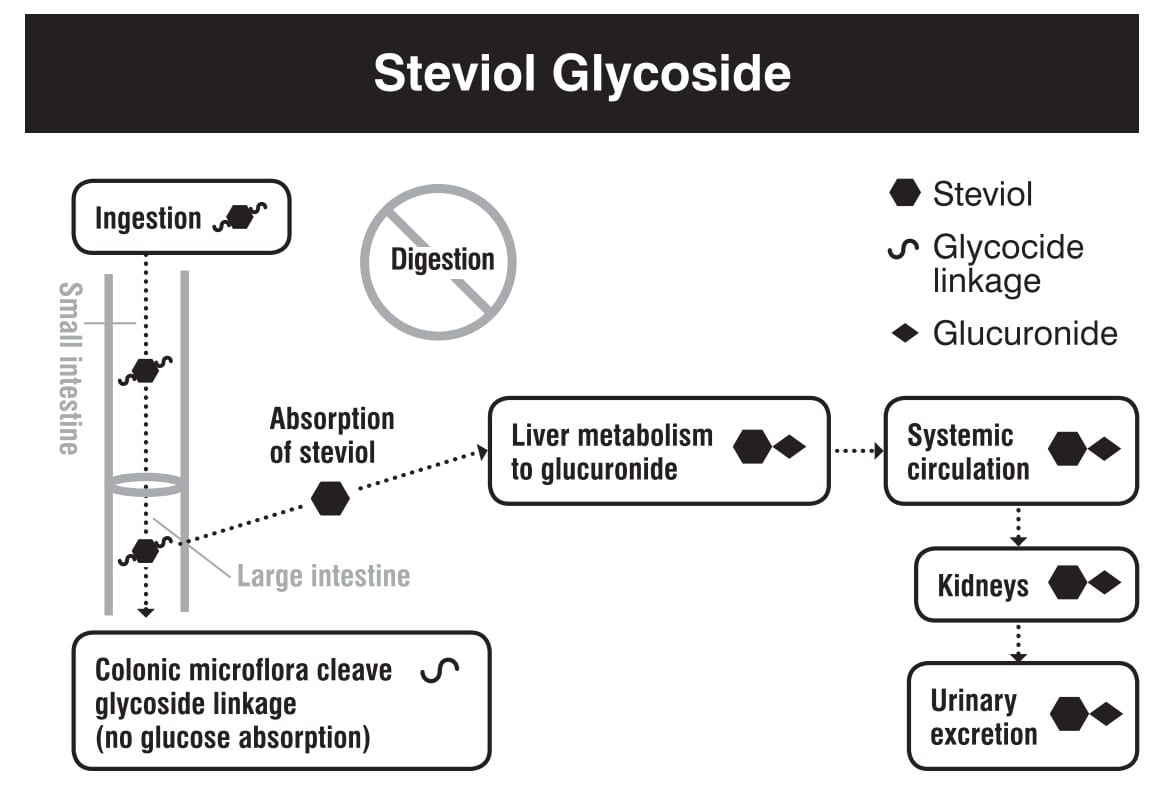

Commonly referred to as Stevia, the sweeteners are actually the steviol glucosides, namely rebaudioside A, from the leaves of the Stevia rebaudiana plant. People commonly assume natural equals safe, but mechanistically, Stevia extract is the only sweetener in this article that the gut microbiota in our colon can significantly feed on. Thus, Stevia extract can directly affect our gut health. Indeed, human and rodent research show that consuming Stevia extract can alter the concentrations of several bacteria in our gut, although the effect is minor. The hydrolysis in the gut leaves a steviol backbone, which is then absorbed from the colon and bonds with glucuronic acid before being excreted as as steviol glucuronide via our urine.

Although Stevia extract can change our gut microbiota and reacts with compounds in our body, it appears to be safe up until the ADI. Stevia extract’s ADI is expressed by the JECFA as 4 mg/kg/d steviol equivalent, which is equal to about 12 mg/kg/d rebaudioside A. It’s hard to do quick math with that and many products don’t report steviol equivalents, but this ADI is relatively low compared to aspartame and sucralose. A 80 kg (176 lb) individual can only consume 12 packets of Coca Cola Stevia extract according to Coca Cola. You probably don’t want to mega-dose Stevia extract anyway though due to its bitter, metallic aftertaste.

Stevia extract provides fuel for several bacteria in our colon and is metabolized in our body. Source

Conclusion

In contrast to media alarmism and 1 highly questionable study on saccharin, many scientific review papers and regulatory agencies agree that commonly used low-calorie sweeteners are safe for human consumption in any commonly used dosages. This includes

- the Federal Department of Agriculture (FDA),

- the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA),

- the National Cancer Institute and

- *takes a deep breath* the Joint Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and World Health Organization (WHO) Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA).

A 2019 review paper‘s conclusion was pretty sweet: “A few rodent studies with saccharin have reported changes in the gut microbiome, but primarily at high doses that bear no relevance to human consumption. This and other studies suggesting an effect of low/no-calorie sweeteners (LNCS) on the gut microbiota were found to show no evidence of an actual adverse effect on human health. The sum of the data provides clear evidence that changes in the diet unrelated to LNCS consumption are likely the major determinants of change in gut microbiota numbers and phyla, confirming the viewpoint supported by all the major international food safety and health regulatory authorities that LNCS are safe at currently approved levels.”

To be safe though, parents of small children and pregnant women should check their consumption against the acceptable daily intake (ADI). If you use a lot of saccharin (still drinking Cola Tab? Get with the times, yo!), you should also check your daily intake and consider switching to aspartame or sucralose. Most people think they taste better anyway and their safety track record is much clearer. You can also go with Stevia extract if you don’t mind its taste, but despite being ‘natural’, its safety track record is actually a bit worse than that of aspartame and sucralose.

Enjoy your sweeteners!

Want more content like this?

Want more content like this?

Then get our free mini-course on muscle building, fat loss and strength.

By filling in your details you consent with our privacy policy and the way we handle your personal data.