Study: Does becoming stronger help make us bigger?

Training program periodization is well established to benefit athletes who compete to maximize performance at the date of competition. However, the literature on periodization for muscle growth is still quite uncompelling. Or maybe I should say ‘was uncompelling’, because a new study by Carvalho et al. (2020) just published very intriguing findings.

The researchers gathered 26 men who could squat at least 1.5x their bodyweight and randomized them into one of 2 programs. Both programs consisted of 4 sets of squats and leg presses performed twice a week with maximal effort, but they differed as follows.

- The hypertrophy (HT) group performed 8 weeks of 4 sets of 8-12 reps with 1 minute rest in between sets.

- The strength-hypertrophy (STHT) group performed 3 weeks of 1-3 reps with 3 minutes rest in between sets, after which they switched to the HT program for the remaining 5 weeks.

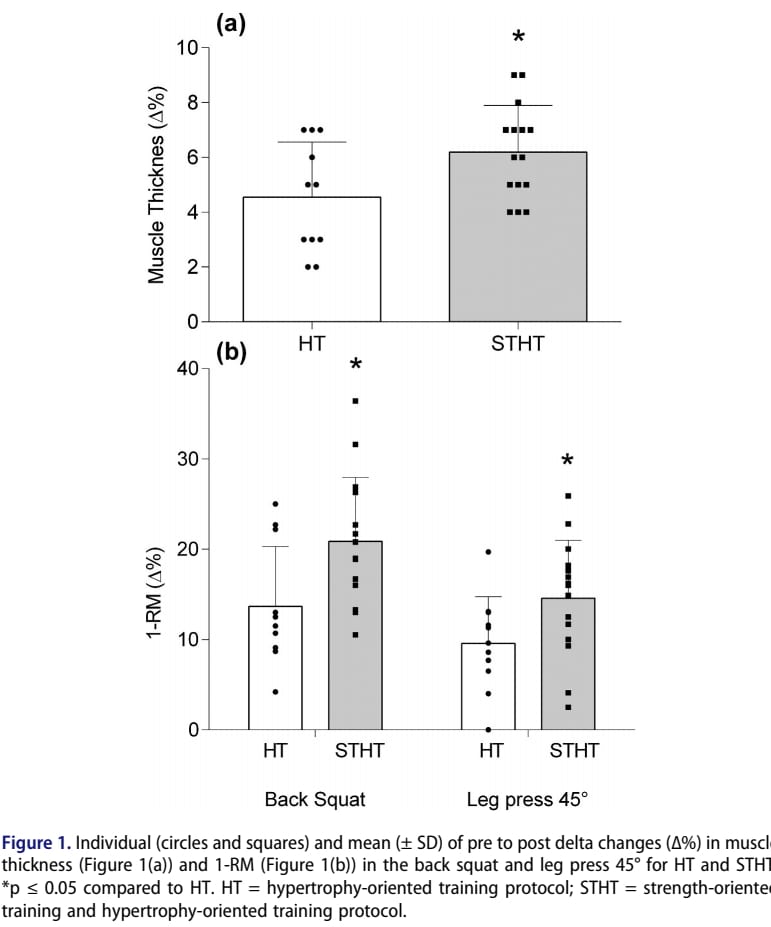

After 8 weeks, the STHT group achieved significantly better strength development (1RMs) and muscle growth (vastus lateralis muscle thickness), as you can see in the image below.

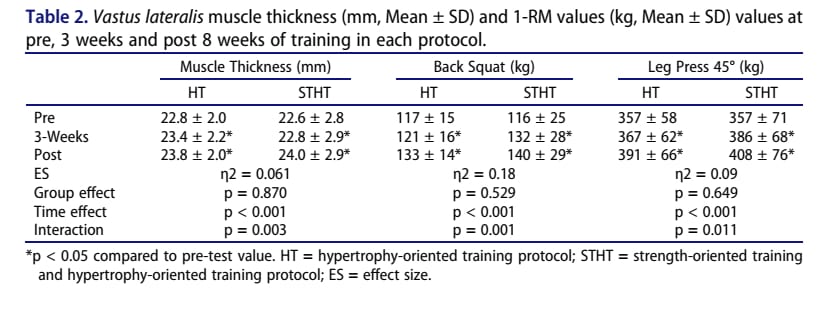

The researchers also measured their gains at 3 weeks into the program. By this time, the STHT group had gained considerably more strength than the HT group but not as much muscle growth. This was exactly as expected: training with 1-3RM loads is great for strength but not for muscle growth. It also makes sense that this phase of greater strength gains translated into greater total strength gains across the 8-week program. However, what happened to muscle growth was quite a revolutionary finding. Despite losing the race at 3 weeks into the program after the strength training program, the STHT group more than caught up in muscle growth over the next 5 weeks. You can see the detailed results in the table below.

(Technical note: The group effect of absolute muscle growth was not remotely statistically significant, but this makes sense, as the STHT group started with a slightly lower baseline muscle thickness value and exceeded the HT group’s value at the study end, this creating a cross-over effect. In these cases, the standard group effect analysis is not applicable and we should look at the group*time interaction effect, which turned out very significant.)

What could explain these findings? The researchers put forth 2 explanations.

Potential mechanism 1: We know muscle growth is primarily stimulated by mechanical tension on the muscle fibers. The researchers argue that using heavier loads increases tension on the muscle fibers and thereby stimulates more muscle growth. However, this would require muscles to be sensitive to absolute tension. I would expect them to only be sensitive to relative tension. If a muscle can produce 100 units of force, it won’t grow from producing 50 units of force for a brief duration. That won’t activate the higher-threshold motor units. However, the muscle clearly grew from producing 50 units of force when it could only produce 50. So I would think total force production per se is irrelevant for muscle growth: muscles should respond only to tension relative to their strength capacity. That’s basically what training intensity defined as a percentage of 1RM strength comes down to.

Potential mechanism 2: Relative tension brings us to the more plausible mechanism of increased muscle activation. The total internal tension a muscle produces comes down to how many muscle fibers are recruited and how fast they’re firing. Total recruitment is determined by the Size Principle: the more force a muscle needs to produce, the more bigger, higher-threshold motor units it activates, increasing the percentage of total muscle fibers producing tension. Total recruitment is not something we can improve much, as it should be maximal even in novice lifters if they train hard enough. But firing frequency we can likely improve more: previous research has found that high intensity training increases voluntary muscle activation more than low-intensity training [2]. However, the literature is mixed about how large this effect can still be in well-trained lifters. It may be exercise and modality-specific, which would mean you’d have to get strong specifically in the exercises you’re going to build muscle with.

Some coaches also argue that novelty of training stimulus could explain these results. I’m skeptical of that, especially as there was no change in exercise selection and this was only an 8-week study. The literature on block periodization – programming different phases with different training emphasis rather than performing a similar program consistently for a long time – for muscle growth is extremely uncompelling. Click here to see a research overview on volume-equated periodization studies in trained lifters from my online PT Course. Excess variation is likely more harmful than beneficial: multiple studies show that organizing your program into different phases, as opposed to 1 optimized constant routine, can be bad for your gains.

- Bezerra et al. (2018) found a trend for greater muscle growth and strength development in a training program where strength, hypertrophy and power work were all completed in the same session compared to the same training split over blocks of hypertrophy, strength and power work. Block periodization thus seemed to perform worse than what’s sometimes called conjugate periodization. The subjects were elderly individuals though.

- Bartolomei et al. (2015) compared an equal total work volume with block periodization program to weekly undulating periodization (WUP) in strength-trained women. The WUD group experienced a significantly and considerably greater increase in their 1RM squat and thigh cross-sectional area. Other measures of power, strength and body composition didn’t differ significantly between groups.

- Gavanda et al. (2019) compared an equal total work volume with block periodization to daily undulating periodization (DUP) in strength-trained adolescent American football players. There were no significant differences between groups in strength (incl. 1RM squat and bench press) or body composition measures. However, there was a trend for the DUP group to lose more fat in effect size analysis and this became significant in post hoc analyses. Effect size analysis also suggested greater total body gains in fat-free mass and muscle mass in the DUP group.

So in terms of practical application, I would actually not recommend doing what this study did: having a pure strength phase in your programs if your primary goal is muscle growth. Rather, what I do in well-trained lifters is to program in some high intensity training, often with reverse pyramiding or post-activation potentiation work, in an overall ‘bodybuilding program’. This helps stimulate strength gains without compromising on muscle growth and should thus result in the best of both worlds. According to the present study, those strength gains may increase long-term muscle growth.

New study reference

Is stronger better? Influence of a strength phase followed by a hypertrophy phase on muscular adaptations in resistance-trained men. Carvalho et al. Research in Sports Medicine: An International Journal. https://doi.org/10.1080/15438627.2020.1853546

Want more content like this?

Want more content like this?

Then get our free mini-course on muscle building, fat loss and strength.

By filling in your details you consent with our privacy policy and the way we handle your personal data.