3 Plausibly potent myths about your posture

Everyone wants good posture. To achieve this, a typical visit to a physical therapist – let’s call our therapist Bob – goes as follows.

1. Bob makes you stand upright and relaxed

2. Bob examines your posture

3. Bob compares your posture to optimal posture

4. Bob prescribes you some exercises and stretches to push and pull your deformed body into a more beautiful form

Sounds fine, right? Plausible and intuitive as this straightforward approach to postural correction may be, scientific research has identified many problems with this approach. In this article I’ll go into 3 prevalent myths about your posture.

Myth 1: You can accurately diagnose your posture from the outside

It seems so plausible. How do you diagnose someone’s posture? Well, you can just look at it, right? You surely get some idea of someone’s posture this way, but this idea is more about someone’s body shape than someone’s internal joint positions. It’s like looking at a house to determine the structure of the foundation. That may be somewhat accurate for very simple box style houses, but when a house has a more complex shape, you can no longer reliably determine its internal structure from its outside appearance.

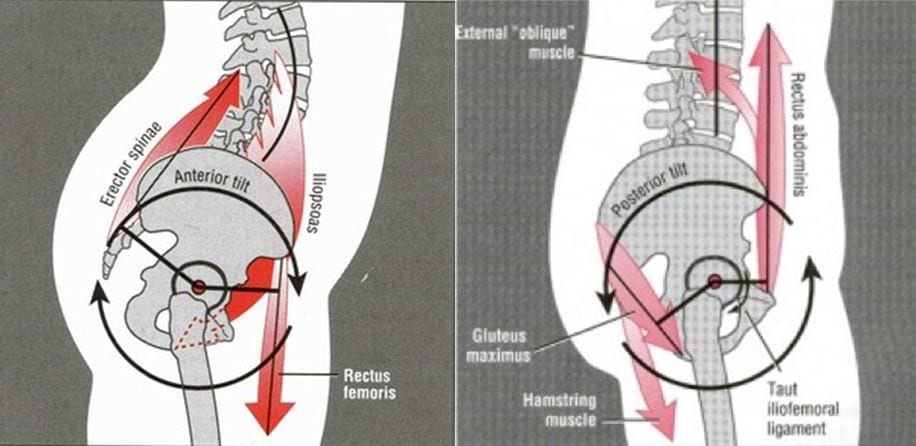

Let’s take anterior tilt, for example. Many people are worried they have too much anterior tilt in their pelvis, which makes their butt and belly stick out, AKA Donald Duck syndrome.

Anterior tilt (left; ‘Donald Duck syndrome’) vs. posterior pelvic tilt (right; during a squat this is often informally called ‘buttwink’)

When you look at someone’s body from the side, you can only get a very rough idea of their pelvic tilt angle. If someone has serious booty and a bit of a pot belly, they may appear to have anterior pelvic tilt even with a neutral pelvis. So many people infer the angle of the pelvis by the angle of the spine. While you often move your spine and pelvis together, posturally speaking, the angle of the pelvis and spine are very poorly correlated [2].

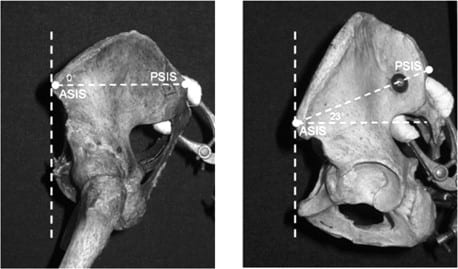

So researchers have come up with a method, using something called the ASIS-PSIS angle of tilt, to determine someone’s pelvic position based on its bony landmarks rather than just visual appearance.

However, even this method is very fallible, because we humans don’t just differ in pelvic tilt angle but also pelvic shape. Variations in pelvic shape can make it appear someone’s in anterior pelvic tilt when they’re actually not. See the example below for 2 pelvises positioned in their neutral position. The left one actually appears neutral and comes out of the test as such with a 0° ASIS-PSIS angle; however, the right one has a massive 23° ASIS-PSIS angle, which would register as major anterior tilt.

So if you were to ‘fix’ this person’s pelvic tilt, you’d actually have to put them in major buttwink and if they’d use that unnatural posture for things like squatting and deadlifting, they could get injured.

2 Pelves, 1 position

In conclusion, the only truly accurate way to diagnose someone’s posture is to do something like an MRI scan. You can’t just look at somebody’s body to accurately determine its internal joint positions.

Myth 2: You have 1 posture

Assuming you have managed to correctly diagnose someone’s posture, that’s just 1 snapshot in time. Basically every time we stand, we stand slightly and sometimes very differently. There is major variability in standing posture not only between but also within individuals: this applies to everyone regardless of whether they’re involved in exercise or whether they have pain. Think of how you stand when you just get out of bed, versus how you stand when you’re public speaking, versus how you stood when your teacher berated you in front of the whole class.

Our posture is significantly related to our psychological state, perhaps more so than our muscular state. For example, we intuitively stand up taller when we feel pride, and we slump more when we feel disappointment.

I suspect the postural improvements I’ve seen in many of my clients actually had less to do with their muscular balance, flexibility and what not and more with greater self-esteem from looking better and feeling more confident about how to control their physique and fitness.

Our dynamic posture – how we move – varies even more so than our resting posture. Researchers and functional training gurus have come up with multiple tools to diagnose how we move. The most popular of these is arguably The Functional Movement Screen (FMS). It’s even taught in some Personal Training certifications. Based on a series of bodyweight stretches and exercises, it diagnoses imbalances.

Sounds great. Doesn’t work. The FMS score is barely more accurate than flipping a coin at predicting injury risk [2, 3, 4] or performance. Movement is a skill, and a highly specific one. So how someone moves on a few rudimentary tests or what their resting posture is says very little about how they move during their sport. You can see gymnasts at the Olympics sitting on the bench with horribly slouched posture before they win a medal. A world-class powerlifter may pick up his gym bag with a majorly rounded over spine yet deadlift 800 pounds with a neutral spine.

Somebody needs to tell these NBA players who make their money playing basketball how dysfunctional their posture is (/sarcasm)

Have you ever tried to fix your squat with flexibility and mobility drills? I’ve been there and I know dozens of lifters who spent hours each week on their mobility and yet they still couldn’t squat properly to parallel. Then you give them 1 good technique session where you address their form issues and boom, they can squat to depth. The only thing that really teaches you how to squat is squatting.

Myth 3: There’s 1 über posture to rule them all

Let’s take postural assessment a step further and say you have diagnosed that someone has a true postural deviation like anterior pelvic tilt based on an MRI scan. Common theory is that you should correct this, because it’s a pathology.

A pathology, from Greek pathos “suffering” + logia “study”, by definition requires symptoms like pain or dysfunction. However, Herrington (2011) found that many people with anterior pelvic tilt do not have any symptoms and many other studies, including a 2008 systematic review, have found no relation between lower back pain and spinal posture, and minimal relation between spinal range of motion and incidence of low back pain [2, 3, 4, 5].

In fact, a 2019 systematic review of systematic reviews found no consistent relation between any type of posture and low back pain.

Anterior pelvic tilt: Donald Duck freak postural monstrosity… or good form?

These findings extend to other body parts as well. A systematic review of longitudinal studies found no relations between back, shoulder or neck pain and muscle strength, balance, endurance or range of motion.

For the shoulder too posture and pain are often unrelated, yet physical therapists tend to diagnose postural abnormalities in the shoulder more often when they know someone has shoulder pain. The same physical therapists in that study correctly diagnosed no differences when they were unaware of the presence of pain. In other words, physical therapists tend to be biased – as we all are – to see imaginary problems that fit the falsified theory they’ve been taught.

Not only are postural deviations not commonly associated with pain, they may be beneficial for athletes.

Watson (1993) found that athletes involved in running sports such as soccer and football show marked anterior pelvic tilt (lordosis) compared to other sportsmen. He also studied the posture of 11 soccer players over 3 years and found the lordosis of 8 of them to be significantly increased with their participation in the sport. Anterior pelvic tilt may be biomechanically beneficial for horizontal force production.

Upper-crossed syndrome also does not seem to be inherently associated with any adverse physical effects. Many boxers and swimmers have forward rounded shoulders and kyphosis (thoracic flexion) without any corresponding issues; in fact, this posture may be advantageous to increase stroke rate in the water according to Bloomfield (1998).

It thus seems that the diagnosis of anterior pelvic tilt is often based on abnormality per se, not the presence of any actual problems and sometimes even when the abnormality may be advantageous. It’s a sad state of affairs if we inherently equate ‘not normal’ with ‘bad’.

And is military posture really normal in the first place? In Herrington’s aforementioned study, 85% of males and 75% of females had an average of 6-7°of anterior pelvic tilt. In the same study, 6% of males and 7% of females exhibited posterior pelvic tilt, while only 9% of males and 18% of females showed a neutral hip position. And again, none of these individuals had any symptoms. Let’s emphasize this: the majority of the asymptomatic population ‘suffered’ from anterior pelvic tilt. So we can’t even say anterior pelvic tilt is abnormal in the first place.

Humans are also not perfectly symmetrical. Knutson (2005) found that 90% of people had a leg length inequality of ~5.2 mm. A difference in how long your legs are is generally not considered a clinical concern up to 2 cm (0.78″).

To conclude, it is time to abandon the textbook myth (ideology?) that all humans should have a certain structure and posture. Humans are natural organisms, not robots produced in a factory. There is no über posture. Unless you actually lack functionality or you’re in pain, you can’t fix what isn’t broken. Embracing your bodily structure will likely improve your posture more by radiating self-esteem than trying to physically fix it. Every body is different and different does not mean worse.

Want more content like this?

Want more content like this?

Then get our free mini-course on muscle building, fat loss and strength.

By filling in your details you consent with our privacy policy and the way we handle your personal data.