New science on the optimal training volume: extreme training for extreme gains?

Most evidence-based fitness professionals recommend a training volume of 10-15 sets per muscle group per week. I’ve recommended 10-30 sets in my interviews the past years for most individuals with some outliers using higher volumes, like IFBB Pro Nina Ross. The truth is, even I may have been overly conservative.

I recently posted the results of a training study co-authored by Mike Israetel in which the participants kept making good progress as they pushed up their training volume to 32 sets of squats per week.

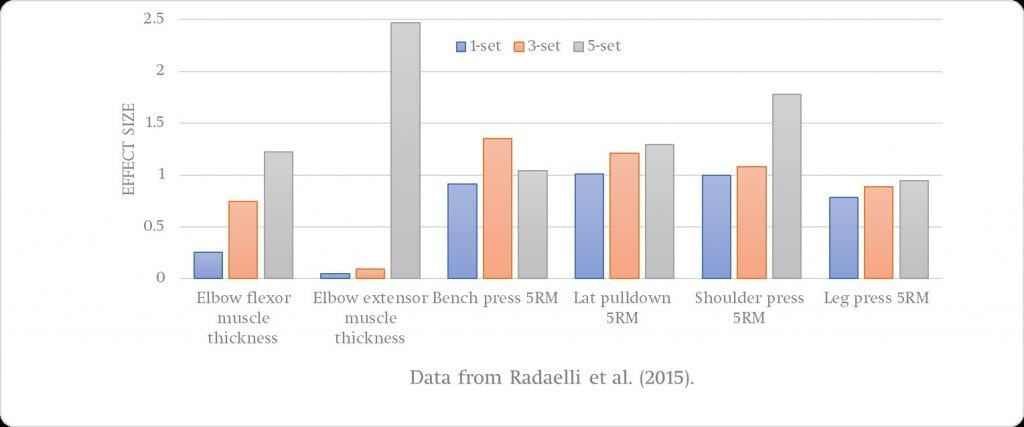

I noted that the claim of the authors that this is the highest volume ever studied isn’t strictly true. Radaelli et al. (2015) had participants perform 1, 3 or 5 sets per exercise with 2 exercises for the biceps and 3 for the triceps in a 3x per week full-body training program. So for the biceps the set volumes per week were 6, 18 and 30; for the triceps they were 9, 27 and 45. All sets were performed to failure. This is probably my favorite study on training volume to date, because they studied such a wide range of volumes, the study lasted 6 full months and the participants were military personnel. Many study populations don’t battle much other than sarcopenia.

With the exception of the bench press, the results for all measures showed a more-is-better dose-response all the way up to the super high volumes, as illustrated below. Note the massive triceps thickness gains from the group performing 45 sets of triceps work per week. There don’t even appear to be diminishing returns for muscle growth. For strength development, the additional gains from more sets were pretty meager though.

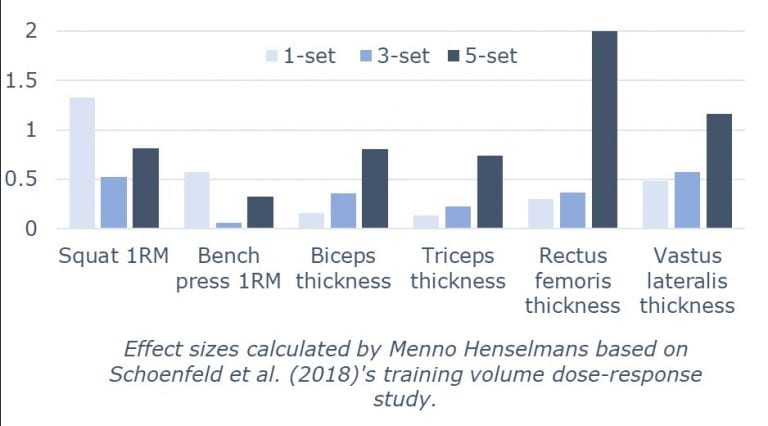

Yesterday Schoenfeld et al. (2018) published a very similar study. Strength-trained men performed 1, 3 or 5 sets per exercise during an 8-week study. This led to a total weekly number of sets per muscle group of 6 and 9 sets for the 1-set group, 18 and 27 sets for the 3-set group and 30 and 45 sets for the 5-set group in the upper and lower limbs, respectively. So training volume was 50% higher for the quads than for the triceps and biceps. All sets were performed to failure.

As illustrated below, there was no effect of training volume on strength development at all, while there was a clear dose-response of training volume with higher volumes resulting in markedly greater muscle growth.

That’s 2 studies supporting the more sets you do for a muscle, the more it grows, up to at least 45 sets per week. To failure. Many coaches debate if there’s a point in doing more than 10 sets per week, so 45 sets to failure sounds ludicrous in contrast. Where does this contrast come from?

Training experience. Most studies are done on untrained individuals. Untrained typically correlates with unmotivated. They can muster up the effort to perform some volume of training, but if they know they have to perform 45 sets a week, they will typically hold back and as they get fatigued, training efforts diminish even further. Physiologically, it also makes sense that the more advanced you become, the higher your optimal training volume rises. Advanced trainees are more resistant to muscle damage and neuromuscular fatigue. Advanced trainees also show a blunted hormonal-anabolic response to a given training volume.

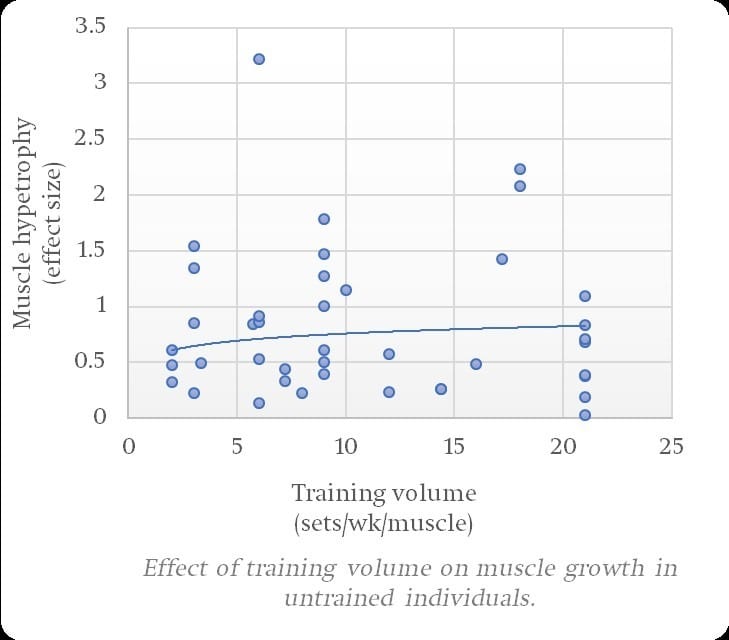

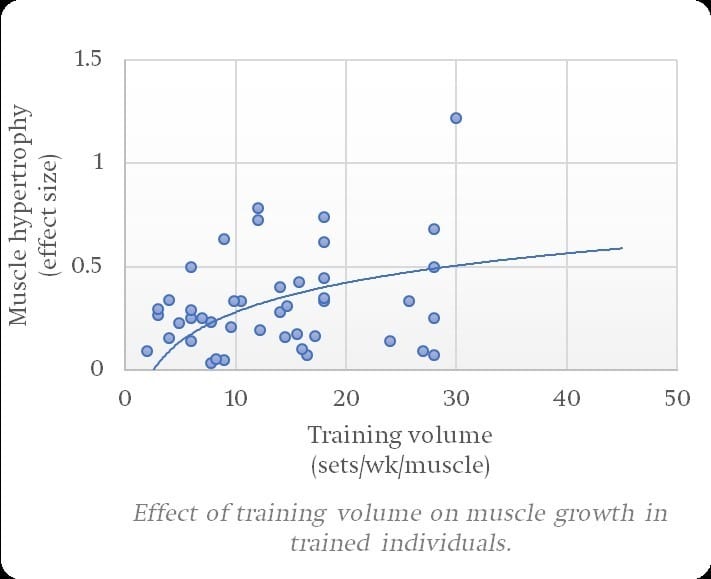

Most analyses don’t separate studies by training experience, so my research team is performing a meta-analysis. We’ve collected every study on training volume ever published worth a damn, calculated the found effect sizes and plotted the results separately for untrained and trained individuals. Negative effects sizes are included but not shown, as they are likely indicative of measurement error or lack of adherence to the training program. If you manage to lose muscle while training without being in energy deficit, something is horribly, horribly wrong.

Here’s what the data show for untrained individuals. The logarithmic best-fit trendline shows an increase in gains from 5 to 20 sets per week, but it’s not exactly major. Notably, the highest effect size is for a very low volume and some of the lowest non-negative effect sizes are for the highest volumes.

Now contrast these results with the studies on trained individuals. These graphs don’t contain Schoenfeld’s last study yet, so if anything, they underestimate the effects of volume. The graph also doesn’t display (but does include) the major outlier of Radaelli et al. as it’s literally off-the-charts high way up in the top right. Even without those, the data beautifully fit a diminishing returns curve. These are also the data I based my traditional 10-30 set range on. Students of my last PT Course will note I’ve updated this range to include higher volume recommendations based on the latest research.

Taken together, these data strongly support the effectiveness of extremely high volume training. Yet many people who have tried such high volumes have run into a wall quickly. I think, based on the literature and my experience helping hundreds of people attain their ideal physique, most people run into the limits of their willpower or connective tissue long before their muscles actually become incapable of recovering from the training volume.

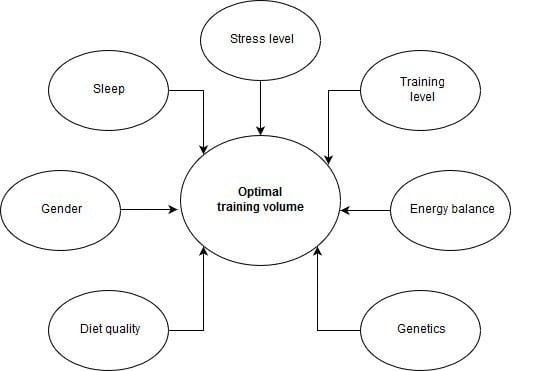

But, and this is a big but – not just a fine squat booty but a Kardashian sized caveat – more volume is not always better. I think you should take into account at least the following factors when estimating someone’s optimal training volume. Other obvious factors like disorders and injuries and at a certain point, age, should be considered too.

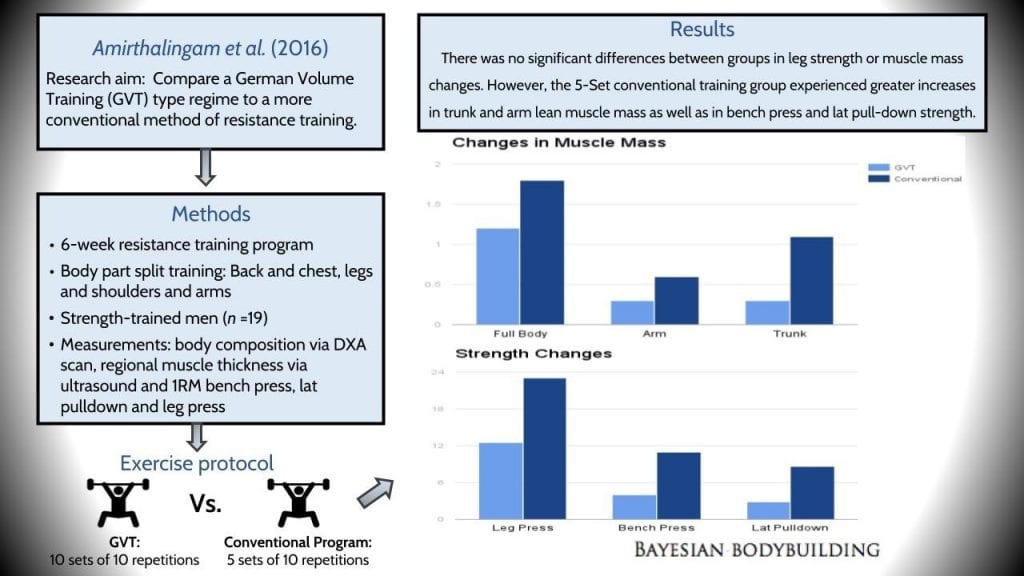

If you don’t take into account someone’s recovery capacity, you may not just be wasting time and effort and risk injury, you may also be directly reducing your gains. Several studies have found that there’s a sweet-spot training volume compared to which, doing more or less, reduces progression [2, 3, 4]. The most well-known of these is the German Volume Training study finding that cutting the volume in half from the original 10-set template improved results, as illustrated below.

I’d also emphasize how important nutrition is for your recovery capacity. To illustrate this, during Ramadan fasting athletes gain strength faster when they reduce their volume by 22% than when they stick with their previous training volume. So no program is optimal for cutting as well as bulking. There really is no one-size-fits-all program.

In conclusion, thou must work hard, if in the Olympia thou want to take part, but thou must also work smart, lest thy body falls apart.

Want more content like this?

Want more content like this?

Then get our free mini-course on muscle building, fat loss and strength.

By filling in your details you consent with our privacy policy and the way we handle your personal data.