What’s the best grip to train your biceps according to science?

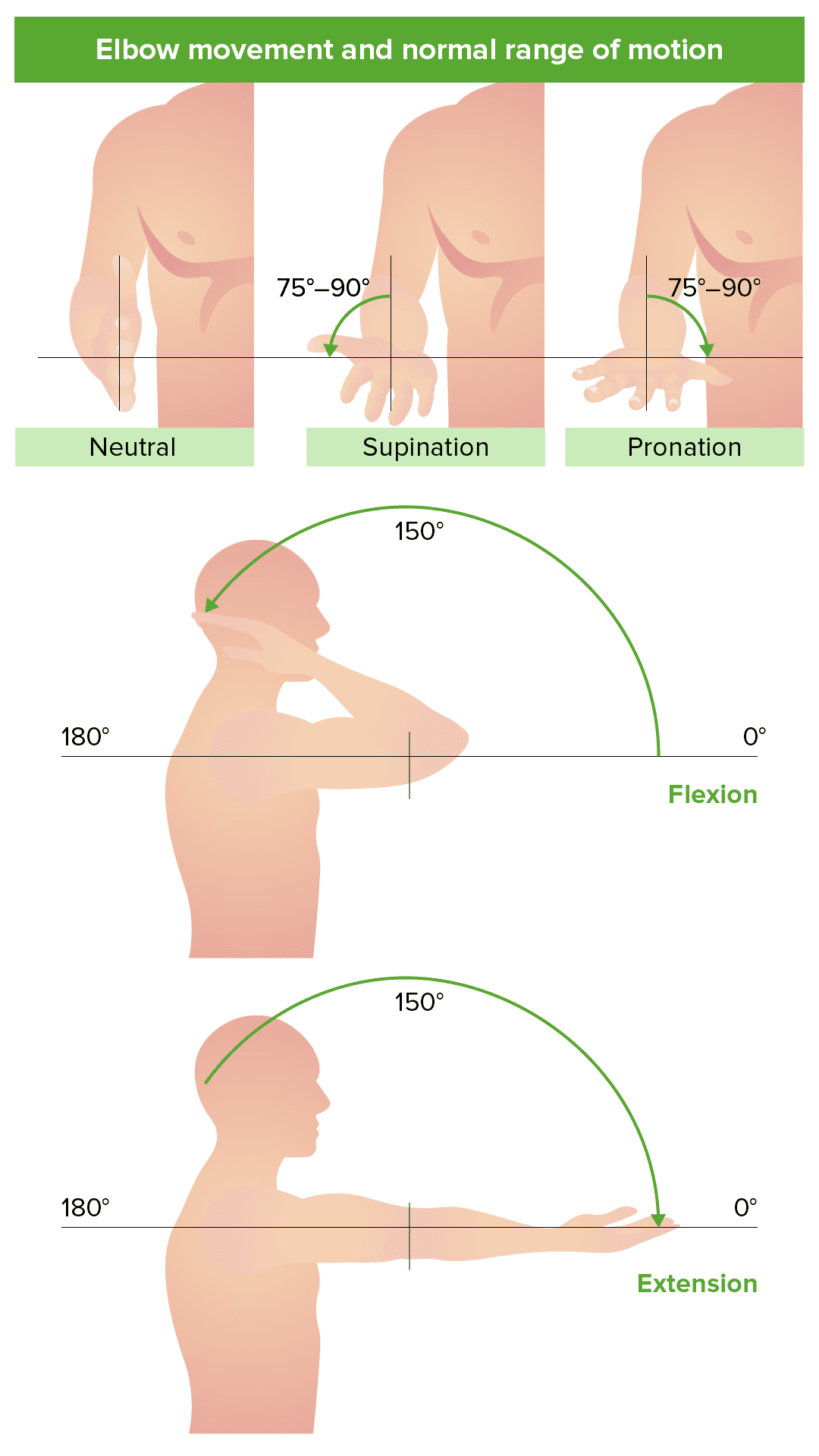

The traditional recommendation to train the biceps is to use a supinated grip (underhand: you can see your palms). This advice is given by both researchers and practitioners based on 3 main arguments.

- The biceps is not just an elbow flexor but also a forearm supinator.

- The biceps has the best leverage for elbow flexion (higher internal moment arm) when the forearm is supinated.

- You feel the biceps the best in supination generally.

Thus, it makes intuitive sense to use a supinated grip. However, most data don’t support the idea that a supinated grip results in higher biceps activity than a neutral or even a pronated grip. Let’s look at what the data and biomechanics really say about which grip is best to train your biceps.

The data

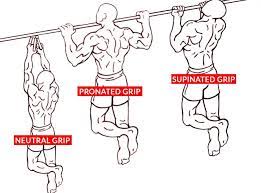

The majority of studies have found no effect of forearm position (supinated vs. neutral vs. pronated with or without rotating handles) on biceps activity during pulldown variations [1, 2] or pull-up variations [1, 2, 3]. The only study that directly supports the use of a supinated grip over a pronated grip is Youdas et al. (2010): chin-ups with bodyweight caused higher biceps activity than pull-ups. Chin-ups with a rotating grip were on par with regular, fixed-bar chin-ups. However, grip width and range of motion (ROM) weren’t standardized, resulting in significantly greater elbow flexion ROM during the 2 chin-up movements, which suggests the pull-ups were performed in a more back-dominant manner by pulling from the elbows. Unfortunately, all these electromyography (EMG) studies were poorly conducted. In particular, they did not equate the training intensity (% of 1RM) in each exercise but used the same weight for all exercises. To the extent that a pronated grip makes you weaker, this biases the results in favor of the pronated grip due to the higher relative load.

However, in some cases the training intensity must have been roughly equal. Dickie et al. (2016) found no significant differences in mean or peak biceps activity between wide, pronated pull-ups and shoulder-width chin-ups with a supinated, neutral or rope grip. Since most people are about as strong with a supinated and a neutral grip, depending on how experienced they are with either grip, the intensity should be similar on average. Biomechanically, a neutral grip should be a bit stronger than a supinated grip, so the neutral grip should result in experience slightly lower muscle activity levels with bodyweight if a neutral grip was really worse for biceps recruitment. Therefore, these results strongly suggest a neutral AKA hammer grip and a supinated grip are equally effective to stimulate the biceps.

Similarly, Lusk et al. (2010) found no difference in biceps activity between pronated or supinated pulldowns, regardless of whether they were performed with a wide or narrow grip. The researchers justified their decision to use the same weight for all pulldown variations by citing that a previous study with a similar design found no significant difference in 1RMs between the different variants. However, this may have been true for weaker individuals, but Lusk et al. studied strength trainees and for these we cannot assume equal strength levels for the different exercises.

The lack of difference in biceps activity with a pronated vs. supinated grip also seems to translate into equal muscle growth. Gentil et al. (2015) compared pronated-grip lat pulldowns to supinated-grip barbell curls and found that they resulted in equal biceps growth. Paulo Gentil’s credibility as a researcher has been questioned though after his unapologetic involvement with Matheus Barbalho, who has had multiple publications retracted for ‘improbable data’ (read: fraud).

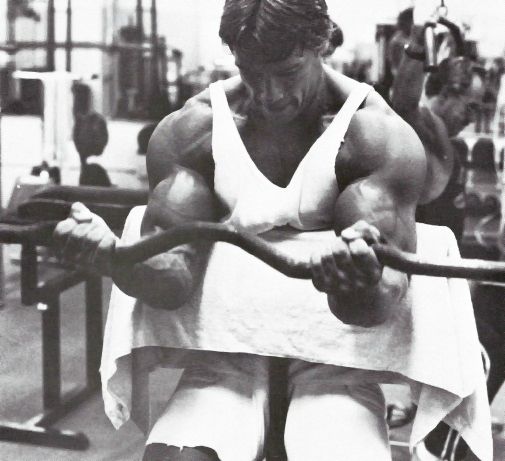

Speaking of biceps curls, we have 4 studies on these that measured biceps activity in strength-trained men while equating the training intensity between the different biceps exercises. In 2018, Marcolin et al. found no significant differences in biceps brachii muscle activity between supinated barbell curls and EZ-bar curls with a semi-supinated grip (see image below for what an EZ-bar is). There was also no significant difference between the grips in the activity of the brachioradialis, another elbow flexor below the biceps on the forearm. Interestingly, both barbell curls tended to result in higher activities than alternating, standing dumbbell curls with active supination. However, this comparison between barbells and dumbbells may have been confounded by greater ROM during the dumbbell curls and their alternating execution. The bottom position of a dumbbell curl has low muscle activity when the biceps relaxes, which brings the average of the movement down. Dumbbells are probably no worse than barbells to recruit the biceps, but they certainly don’t appear to be any better based on this study. Active supination thus does not seem to enhance biceps recruitment, in line with the aforementioned studies finding that rotating grips during pulldowns and pull-ups also don’t enhance biceps activity.

In 2019, Bagchi & Raizada again found no significant differences in muscle activity of the biceps or brachioradialis between EZ-bar and regular barbell curls. They tested the difference at 3 grip widths. This study wasn’t great though. Only 1 rep was performed and it seems they used the same weight for all exercises

A new study on 10 competitive bodybuilders by Coratella et al. (2023) also compared supinated grip barbell curls to EZ-bar curls performed either with or without simultaneous 30° shoulder flexion (letting the elbows come up a bit during the curl). The straight bar resulted in 1.8% higher biceps activity compared to the EZ-bar during the concentric phase (lifting the weight), which was somehow statistically significant, but not the eccentric phase (lowering the weight). With simultaneous shoulder flexion, the difference disappeared during the concentric phase but became significant somehow during the eccentric phase at +3.8%. Statistical significance aside, these differences are too inconsistent and too small to be practically meaningful I would say.

Finally, another new study by Coratella et al. (2023) on the same 10 bodybuilders compared a supinated bar, pronated bar and neutral rope grip during cable curls. The choice of cable curls as opposed to dumbbell or barbell curls is really unfortunate in my view, especially considering they didn’t standardize the distance to the cable tower or the ROM, both of which can make a substantial difference to how difficult the exercise is. Moreover, it’s unclear if 8RMs were conducted for each exercise, as they talk about a single 8RM yet say it was done with ‘the technique described above’, which referred to the 3 different exercise techniques. They also trained submaximally, performing 6 reps and discarding the first and last reps. As a result, the results were quite odd. The main result seemed to vindicate the supinated grip for the biceps. Biceps activity was highest in order of supinated > neutral > pronated. However, this was only true for the ascending phases: there were no significant differences for the descending phase. In contrast to the idea that recruitment follows leverage, brachioradialis activity was also greatest with a supinated grip yet equal between neutral and pronated grips. Again, there were no differences in brachioradialis activity during the descending phase, only during the ascending phase. Weirdest of all, front delt activity was significantly higher with the pronated and neutral grips than the supinated grip. The trend was pronated > neutral > supinated for both the ascending and descending parts of the lift, although during the descent only the pronated grip significantly differed from the other 2 grips. The difference in shoulder activity suggests the trainees moved their elbows forward with the neutral and pronated grips or perhaps were at different distances from the cable tower, which may explain their lower biceps recruitment. All in all, it’s unclear exactly how the exercises were performed, the results don’t make biomechanical sense and they conflict with the research on pulldowns and pull-ups, so I’m not sure how much stock to put into these findings.

How come the majority of data don’t align with the ‘supinated grip is best for biceps building’ hypothesis? It’s because the idea doesn’t make biomechanical sense.

The biomechanics

You may feel your biceps more, or just see it more, when your forearm is supinated, because this makes your biceps pop out. The biceps’s characteristic bulge when flexed is because the muscle is bunched up together. This may feel nice and strong, but in reality, it’s the result of the biceps being shortened. And shortened is bad for the biceps’s ability to produce tension, which is the primary stimulus for muscle growth. As I explained in my article on Bayesian curls, the biceps is a relatively unique muscle that can produce the most passive and active tension at near-maximal lengths. Shortening it significantly reduces its ability to produce tension.

Many people confuse internal moment arms with the length-tension relation when it comes to muscle tension. They think the body will recruit the biceps more when the forearm is supinated, because the biceps has better leverage (a greater internal moment arm for elbow flexion) when the forearm is supinated. And it’s true that during many (submaximal, compound) exercises, the brain will preferentially recruit muscles and fibers with the best leverage for the job. This is efficient. However, in the case of an isolation exercise performed near failure, leverage should be irrelevant. The body should maximize the recruitment of all elbow flexors when the task is pure elbow flexion and you train close to failure with good technique. In this case, it’s all muscle fibers on deck, regardless of their leverage. Leverage changes how much you can lift, not how much tension the muscle produces. Tension is primarily governed by the length-tension relationship, which in the case of the biceps actually means that supination reduces the tension on the biceps. Thus, a neutral or even pronated grip may even stimulate greater active tension, as well as stretch-mediated hypertrophy.

Conclusion

Any effects of forearm position on biceps activity seem to be inconsistent and small. Thus, the classic supinated grip is probably not superior to a neutral grip or even a pronated grip to recruit the biceps. In turn, these alternate grips have the advantage of lengthening the biceps, which should increase mechanical tension and may stimulate stretch-mediated hypertrophy, even if you don’t feel the biceps as much subjectively. Using other forearm positions may also change which muscle fibers are most engaged during your biceps work. If you only train the biceps in positions of supination, you may be leaving gains on the table. Your elbows will probably also appreciate some relief from all the supinated curls. So implement some neutral/hammer grips and pronated/reverse grips in your program to build those biceps. Remember: it’s almost summer and when the sun’s out, it’s time for the guns to come out.

Want more content like this?

Want more content like this?

Then get our free mini-course on muscle building, fat loss and strength.

By filling in your details you consent with our privacy policy and the way we handle your personal data.