Optimal program design 2.0

Everything the bros told you about how to train was wrong. Ok, not everything, obviously, but quite a lot of “everyone knows this” ideas turned out to be wrong. And after having lived and trained in over 50 countries, I think I know why.

The origin of broscience

People often ask me how they train in Taiwan or Ecuador or some other exotic location. In my observation, gym bros and bodybuilders all train pretty much the same way everywhere. Lots of partial reps, training to failure, moderately high rep sets, training a muscle infrequently with short rest periods (or they try if they’re not too gassed).

Why? They train intuitively. That means they base their training on what they can concretely observe and feel, in particular the pump and burn you get during training and soreness the days after. You know what you cannot observe well? Muscle growth itself. Yeah, you think you can, but it’s too slow of a process that takes too long and is too subjective to observe. You think partial rep curls are the key to a big biceps? Maybe they just gave you a big pump which you mistook for muscle growth. You think those stiff-legged deadlifts are the best hamstring builders? Maybe they just caused major muscle soreness and you mistook the swelling for muscle growth. A large part of the ‘muscle growth’ that occurs during the early stages of strength training is actually edema: water retention caused by muscle damage, not growth of the muscle tissue itself. Even if you’re actually tracking your body circumferences over many months of training, there are several problems with this little n = 1 case study.

- Going on a higher-carb diet increases intramuscular glycogen stores, which attracts a lot of water into the muscles, ~3 grams per gram of glycogen. It’s not uncommon for a guy to gain 4 pounds of what looks like muscle when they go from a low- to a high-carb diet. This is probably the main reason high-carb diets are so popular among bodybuilders and it makes it incredibly hard to see if you’re looking bigger because of your training or because of your higher carb intake.

- Total energy intake has a similar effect. Even if you stick with your high- or low-carb diet, you’ll lose size when cutting and gain size when bulking and it’s not nearly all actual muscle size. A lot of it is just water.

- The bigger you get, the slower your gains come. There are strong diminishing returns to training as you approach your genetic muscular potential. Did your former program work better because it was actually better or were you just reaping newbie gains with it?

Hell, even if all your friends at the gym join in for the experiment and you randomly split them up into 2 groups, one training with style X and the other training with style Y, and you meticulously control their diets and track their muscle growth with an MRI machine, it may still not be clear what the best training style is. Exercise scientists face this problem every day. Because people grow at such different rates and there are so many variables to control that the field of exercise science suffers from very low statistical power: it’s hard to isolate the effects of one variable with confidence.

In short, anecdotal observation is an extremely crude tool to determine how to train or diet for muscle growth. It can very roughly tell you if something works or doesn’t work, but trying to optimize a training program based on anecdotal knowledge is like performing plastic surgery with a kitchen knife. It doesn’t always work out (no pun intended). So instead of being able to learn from objective feedback, bodybuilders can only rely on the acute feedback they do get, and that’s mostly just whether they feel something in their muscles.

And that’s why when they try to rationalize their arguments with silly pseudoscience, we now call this broscience.

Fortunately, after several decades of scientific research we can now talk about optimal training program design with a lot more evidence than “But the big guy at my gym said…” In this article I’ll cover some of the major broscience myths about how you should train to get jacked.

Rest intervals: how long should you rest in between your sets?

Traditional bro wisdom holds short rest periods of 1-3 minutes are optimal for bodybuilding. There never seemed to be much of a formal argument for why other than that people traditionally trained this way. The real reason was probably that bodybuilders chased the pump and burn they get from shorter rest periods. Later the idea of chasing the pump was rationalized into the theory of metabolic stress. Yet there wasn’t a single study to support that shorter rest periods actually benefit muscle growth.

- In 2005, Ahtiainen et al. found similar muscle growth when training with 5 vs. 2-minute rest periods. Importantly, this study was work equated, which meant the shorter rest period group performed an average of one extra set for each exercise to compensate for their lower work capacity.

- In 2009, Buresh et al. actually found greater muscle growth in a strength training program with 2.5-minute rest periods than the same program performed with 1-minute rest periods.

- In 2010, De Souza et al. found similar muscular development in a group resting a consistent 2 minutes compared to a group gradually cutting their rest periods down to 30 seconds over the course of the program. These results were replicated by Souza-Junior et al. in 2011.

- Later in 2014, Schoenfeld et al. compared 2 work matched programs – a ‘powerlifting type’ program of 7 sets of 3 reps with 3-minute rest periods and a more traditionally bodybuilding type program of 3 sets of 10 reps with 1.5-minute rest periods – and found similar muscle growth.

Yet the idea that short rest periods were best for bodybuilding lived on. Several review papers even recommended rest periods of 30-60 seconds and the American College of Sports Medicine recommended 1-2-minute rest periods with some exceptions up to 3 minutes. So in 2014 I wrote a review paper together with Brad Schoenfeld critiquing the theory of short rest periods for muscle growth and metabolic stress. In addition to a formal overview of the literature showing no empirical evidence that short rest periods maximize muscle growth, my critique was, in short, as follows. The benefits of short rest periods were theorized to result primarily from increased anabolic hormone production. However, production of the key anabolic hormone testosterone is overall unaffected by rest interval length. It is only growth hormone production that increased and only with rest intervals below 1 minute. Problematically, resting less than 2 minutes also increases cortisol production and thereby worsens the T:C ratio. Since there is good evidence the T:C ratio is related to muscle growth, whereas growth hormone is not anabolic in muscle tissue but mostly related to anaerobic fuel mobilization, the hormonal milieu resulting from short rest intervals is more likely to be detrimental than advantageous for muscle growth.

Our paper became very popular and is still in the 5% most popular scientific papers on Altmetric. But public opinion now swung in a direction we didn’t intend to: people concluded it doesn’t matter at all how long you rest.

To settle the matter, in 2015 Brad Schoenfeld et al. and yours truly performed a randomized controlled trial comparing strength training programs with 1 and 3-minute rest intervals. The 3-minute rest group achieved greater muscle growth. While the 1-minute rest group (presumably) achieved greater metabolic stress, it evidently didn’t lead to more muscle growth, less even.

Subsequent research confirmed that resting only a single minute compared to 5 minutes between sets of leg extensions blunts anabolic signaling and acute myofibrillar protein synthesis in the muscle cells in spite of higher metabolic stress in the short-rest group.

Then Fink et al. (2016) showed that when total work is equated, resting only 30 seconds with 20RM loads is just as effective for muscle growth as resting 3 minutes with 8RM loads. The short rest group experienced greater muscle swelling and growth hormone production post-workout, but this was not correlated with muscle growth.

In conclusion, your rest interval matters primarily because it affects your training volume. As long as you perform a given amount of total training volume, it normally doesn’t matter how long you rest in between sets. If you don’t enjoy being constantly out of breath and running from machine to machine, it’s fine to take your time in the gym. It’s the total volume, not how you distribute it over time, that determines the signal for muscle growth. However, in practice, ‘work-equated’ doesn’t exist, as it’s just you, so resting shorter for a given amount of sets decreases how many reps you can do in later sets and thereby your training volume. This means for most people, resting only a minute or less in between sets is probably detrimental for muscle growth rather than beneficial. Programs with short rest periods only work if a large amount of total sets are performed to compensate for the low work capacity you’ll have when you’re constantly fatigued. On the other hand, if you’re already on a high volume program and you increase your rest periods, this could result in overreaching and reduce muscle growth.

Training frequency: how often should you train a muscle per week?

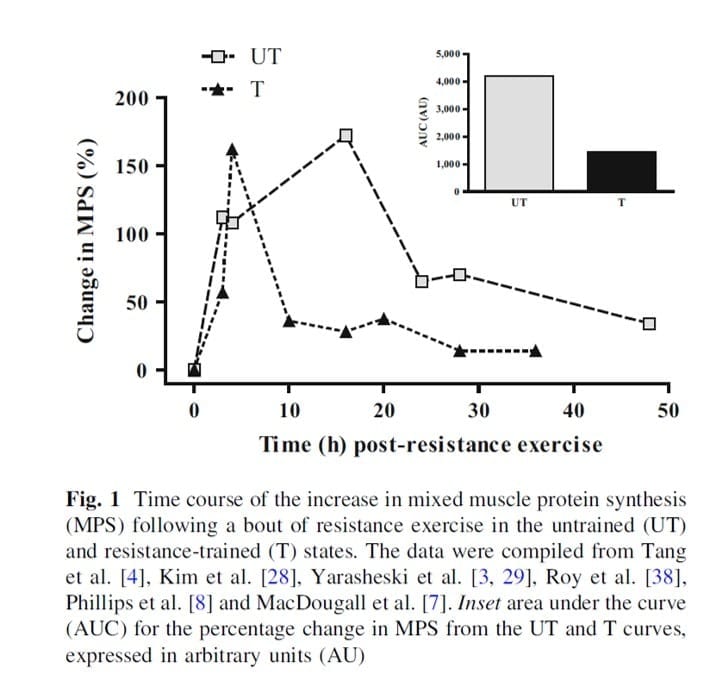

Bodybuilders traditionally train a muscle just once a week. This way you get a huge pump during the workout and a lot of soreness afterwards. Yet we now know that a big pump and sore muscles, or their rationalized variants, metabolic stress and muscle damage, do not equate to muscle growth. In fact, we have good evidence that training a muscle just once a week doesn’t cut it for maximum growth, because your muscles don’t grow that long after a workout. Just think about it: the time-course of muscle growth happens to be exactly the same length as what we define as a week in the Gregorian calendar? I think not. No, many studies have measured the process of muscle growth in the form of muscle protein synthesis after a workout. Damas et al. compiled many of them in the following graph:

As you can see, the time a muscle grows after a workout is unlikely to last beyond 72 hours. It may be possible to increase the length of this period – the anabolic window – by performing a very high volume of training, but several studies of trained individuals find that you get better results by splitting that same total volume over multiple sessions across the week.

- McLester et al. (2000) compared a training program performed as either one large full-body workout or split over 3 full-body training sessions per week. Lean body mass increased by 8% in the 3-day group compared to a mere 1% in the 1-day group. (Not statistically significant but the researchers called it a definite trend consistent across all measures.)

- Schoenfeld et al. (2015) found significantly superior muscle growth for a 3x per week full-body training group compared to a bro-split hitting each muscle twice a week. (The authors said the split group trained each muscle once a week, but look at the actual splits and you can see the arms were trained on arm days and on push/pull days.)

- Heke (2010) also compared a 3x per week full-body training program with a bro split where each muscle was trained only once a week. The full-body group experienced a 0.8% increase in fat-free mass and a 3.8% decrease in body fat percentage, compared to only a 0.4% increase in FFM and a 2.2% decrease in BF% in the bro split group. The differences weren’t statistically significant, but that was probably mainly because these were men benching over 4 plates and the study lasted only 4 weeks.

(Yes, trained individuals can gain muscle and lose fat at the same time.) - Crewther et al. (2016) studied rugby players performing 3 workouts as either full-body workouts or in an upper/lower split, so the weekly training frequency was effectively 3x vs. 1.5x. The full-body group lost more fat (diets weren’t controlled) and gained a non-significantly greater amount of muscle (1.1% vs. 0.4% FFM).

In conclusion, for maximum muscle growth you’ll probably need to train each muscle at least twice a week. A bro split where you hit each muscle just once a week doesn’t cut it. In fact, most of the debate currently centers on whether considerably higher training frequencies than twice per week are even more beneficial. I’ve recently reviewed several new studies on this that you can read here.

Training intensity: how many reps should you perform per set?

This question can be reformulated as: what’s the optimal training intensity? Training intensity in exercise science is confusingly defined as the percentage of your one repetition maximum (% 1RM) with which you’re training. I prefer the terminology relative load, as it’s unambiguous and precise, but terms only ever mean what people think they mean, so let’s stick with the term intensity here. Training intensity should be distinguished from training intensiveness, which is a subjective measure of how effortful the training feels.

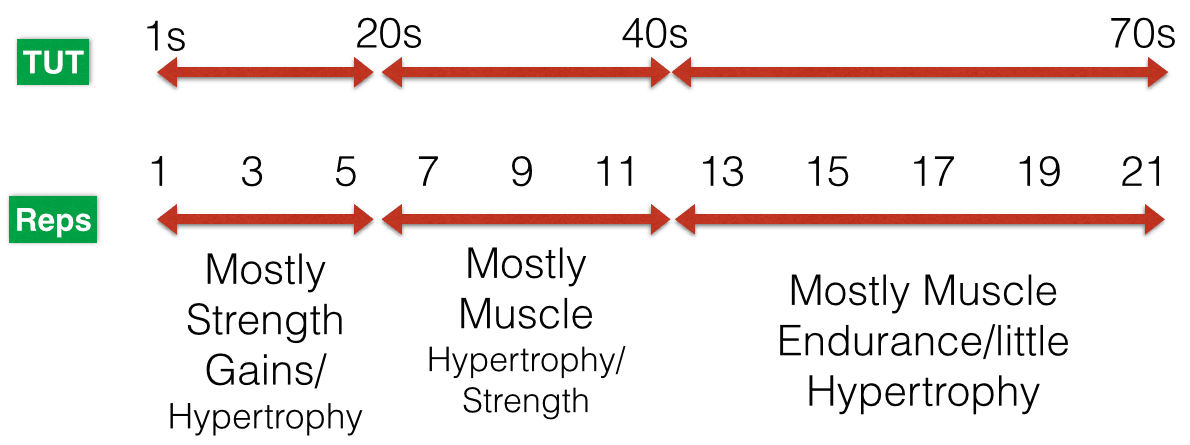

The traditional bro bodybuilding answer is that 6-12 reps is the hypertrophy range, with lower reps mainly benefiting strength and higher reps mainly benefiting endurance. You’ve probably seen images like the one below illustrating the idea of the hypertrophy zone.

The hypertrophy zone: just because someone turned it into a fancy image doesn’t make it true.

Just like for the bro split and short rest periods, there has never been much evidence to support the existence of the hypertrophy zone, especially not the low end. Why would a heavy weight be less effective to stimulate muscle growth than a lighter weight? Well, you don’t feel it. Moderate rep ranges result in a good pump. Higher reps can too, but they can also feel like cardio and the first reps you don’t feel yet. The weight feels too light when you pick it up. Probably based mostly on that feeling, people put hypertrophy in the middle of the strength-endurance continuum. The problem is that strength and endurance are measures of performance, whereas muscle hypertrophy is structural change in the body. They’re different things and they’re not mutually exclusive. In fact, muscle hypertrophy inherently correlates with strength, because an increase in a muscle’s cross-sectional area increases its potential for force output.

Feelings aside, let’s look at what the evidence says. All the way back in 2002, Campos et al. found that a supposedly strength focused program of 4 sets of 3-5 reps results in just as much muscle growth in all muscle fibers as a supposedly bodybuilding focused program of 3 sets of 9-11 reps.

An abundance of subsequent research has confirmed that a given volume of low and high rep work are equally effective for muscle growth. Moreover, in 2012 the hypertrophy zone idea really started to crumble, as Stu Phillips popularized Mitchell et al.’s findings that training to failure with a mere 30% of 1RM result in just as much muscle growth as training with 80% of 1RM. Subsequent research has again confirmed these findings, notably several studies from Brad Schoenfeld’s lab. We now have strong evidence that the hypertrophy zone is more like 30-85% of 1RM or around 5-30RM rather than 6-12RM. Heavier weights are fine too, but you may need additional sets to get enough total time under tension for maximum growth.

Moreover, limiting yourself to the broscience ‘hypertrophy sweet spot’ may be detrimental. While the evidence is weak and not all research supports it, some research suggests training with a wide range of rep zones result in more muscle growth than always sticking with 8-12 reps per set. This may be because you need a variety of rep ranges to maximize growth in all types of muscle fibers. There are also other reasons to vary your rep ranges or use higher or lower loads. An obvious one is that heavier weights are better for strength development and muscle activation, which may in turn increase muscle growth in the long run. Moreover, using a variety of rep ranges could enhance fatigue management, as different rep ranges differ in the kind of fatigue they produce. Higher reps can be particularly useful to prevent overuse injuries, as their produced metabolic stress favorably alters the ratio of muscle to connective tissue stimulation: higher reps are easier on your joints.

In conclusion, do not limit yourself to the supposed hypertrophy range. It may be outright detrimental and it greatly limits your training design options for no reason. Sets of 6-12 reps are not inherently better at stimulating muscle growth than that same volume of heavier work or the same amount of sets performed close to failure with lighter loads.

Should you train to failure?

Many bodybuilders train to failure. No pain, no gain, right? And those last reps give you the best pump. Arnold Schwarzenegger famously summed up the ‘no pain, no gain’ mentality.

It’s an admirable mentality, but do your muscles agree? No, at some point in the set your muscles typically get the hint and you don’t have to trash them further. Several studies have found you get the same muscle growth by training to ‘volitional interruption’, meaning when you feel like you’re done and you intuitively stop, as you get with training to complete momentary muscle failure.

Now, it’s not that training to failure is a complete waste of effort. Some research finds training to failure does increase muscle growth compared to the same amount of sets not taken to failure. The benefit seems to simply be the result of the extra reps you do, as completing the same repetition volume by adding more submaximal sets can achieve the same amount of muscle growth. And there is a big cost to the beneficial effect of training to failure. Training to failure greatly increases the amount of fatigue you induce and the subsequent recovery time your muscles need.

In conclusion, you don’t have to take all your sets to failure. While training to failure can be beneficial, your total training volume is what matters most. As long as you achieve the same overall stimulation of your muscles, you can get the same results with submaximal training.

Conclusion

Beware of basing your training program on how it feels. Let your decisions be guided by reason and evidence. Trust in science. Get fucking jacked.

Did you like this article? Then you’ll love our online PT Course.

Want more content like this?

Want more content like this?

Then get our free mini-course on muscle building, fat loss and strength.

By filling in your details you consent with our privacy policy and the way we handle your personal data.