How to stick to a diet or workout plan, according to science

This is a guest article by Henselmans PT Course student John Fawkes. It aligns well with the psychology and compliance topic from the course. It’s nearly 7000 words long and quite academic, but if you’re interested in behavioral psychology, this will float your boat. If you’re just interested in the take-home messages, there’s a summary at the end.

– Menno

The fitness industry has a dirty secret: for all the time we spend talking about the best exercises, the best diets to follow, and the best ways to plan your workout progressions and macrocycles, we’re not really addressing most people’s fundamental problem. Because what we all know, whether we say it or not, is that most people don’t need a better program nearly as much as they need to be better at sticking to the program they have.

As it happens, tens of thousands of research papers have been published about how to get people to stick to their diet, consistently get more exercise, and develop greater self-control. There are a myriad of proven approaches to improving program compliance: avoiding temptation, smart use of incentives, learning to enjoy healthy food more, and even just straight-up tricking your brain into thinking you’re full.

First, a note: this article is written to be program-agnostic. I won’t get into questions about which diet is easiest to follow, or whether Crossfit is more or less motivating than traditional gym programs. This article will focus solely on techniques, strategies and mental shifts that can be used to improve your adherence to any diet, workout routine, or health program.

With that said, here’s what science has to say about how to stick to your fitness program.

Ego depletion: Willpower as a (possibly) limited resource

Right now, the leading theory about willpower or self-control is something called ego depletion. According to this theory- which is disputed, but I’ll get to that in a bit- willpower is somewhat akin to the stamina bar in a video game. You deplete it when you perform difficult tasks, and can replenish it by resting or consuming food and beverages.

According to Roy Baumeister, the originator of this theory, “A program of laboratory studies suggests that self-control depends on a limited resource, akin to energy or strength. Acts of self-control and, more generally, of choice and volition deplete this resource, thereby impairing the self’s ability to function. These effects appear after seemingly minor exertions because the self tries to conserve its remaining resources after any depletion. Rest and positive affect help restore the self’s resources.”1

This theory has been born out by numerous other studies. However, all of these studies use more or less the same methodology: the experimental group performs a difficult task to deplete their self-control, then performs another challenging task in which their self-control is measured. The control group only performs the second task.

In one of Dr. Baumeister’s early experiments, subjects who had to resist the temptation of eating chocolate subsequently performed worse on a puzzle-solving task. It is notable that most experiments induce ego depletion via a different type of task than the one being used to measure self-control. This strongly supports the notion that self-control is a single capacity that is used for all types of tasks- that is, you use the same resource to resist eating junk food that you use to concentrate on working.

Other studies have suggested that the mechanism behind ego depletion may be glucose depletion in the brain.2 Experimental evidence suggests that restoring glucose levels- either via consuming glucose or simply resting for a while- also restores self-control.

This of course begs a question: what about ketogenic dieters? Does being in ketosis, and keto-adapted, raise or lower your willpower? This question does not seem to have been studied yet.

It may be irrelevant though, because there’s one big problem with these studies: it’s hard to see how the brain could really be using all that much glucose. Your brain uses about 20-25 calories an hour when you’re at rest. Even if you’re exerting yourself mentally, the ego depletion tasks used in these studies should only burn about 5-20 calories at the absolute most. Granted, maybe some specific brain cells are getting glucose depleted, even if the brain as a whole isn’t….maybe. Even then, a few minutes of rest should be enough for those cells to be resupplied with glycogen from the liver; drinking extra sugar shouldn’t be necessary given the small number of calories involved.

Other studies may shed some light on the glucose question. Several studies have found that either consuming artificial sweeteners, or rinsing the mouth with sugar and then spitting it out, have the same effect.3 A separate meta-analysis using a statistical technique called p-curve analysis found that the effect sizes reported for studies examining the link between glucose and willpower is likely being influenced by publication and reporting bias, and that even when statistically significant results are found, their evidentiary value is weak.4

At least one other study has found that inducing a positive mood via watching a comedy video or receiving a gift can counteract the effects of ego depletion.5 This, combined with the study showing that merely tasting sugar without swallowing it can replenish willpower, suggests that the mechanism of action involved may be enjoyment rather than glucose replenishment.

Finally, one study has suggested that willpower is only a limited resource if you believe it is. This study found that students who viewed willpower as a non-limited resource procrastinated less and got better grades than students who viewed it as a limited resource.6

So you just need to change your beliefs about willpower, right? Well, not so fast. This study examined student’s pre-existing beliefs without manipulating them in any way, so it didn’t prove causation. It could well be that the students who viewed willpower as unlimited took that view precisely because they have better self-control, and not that they have better self-control because of their beliefs about how willpower works.

These studies may also be affected by the college student problem. College students may have more or less self-control, or different beliefs about self-control, compared to either older people or people who never go to college.

Given the use of college students as subjects, studies on this subject could also be thrown off by their timing. If the study takes place as finals are approaching, students may well be ego depleted already, and participating in the study because they desperately need the extra credit. On the other hand, if the study takes place right after spring break, the subjects might be in an ego-replenished state after a fun week of doing keg stands and flashing complete strangers.

But there are bigger issues at play here. Several meta-analyses have cast doubt on the validity of ego depletion. According to a 2015 study, “We find very little evidence that the depletion effect is a real phenomenon, at least when assessed with the methods most frequently used in the laboratory.” 7

An article on slate.com sums up the problems with ego depletion research so far. Meta-analyses that support the theory include only published studies, introducing a large degree of publication bias. Meta-analyses that include unpublished studies find little or no effect. In one replication study, only 2 out of 24 research teams running the exact same experiment found a significant positive result.

Different studies on ego depletion also use conflicting and sometimes unfounded measures for ego depletion; one study assumed that ego-depleted subjects would give more money to charity, while another assumed they would spend less time helping a stranger.

In short, the sum total of evidence suggests that willpower either doesn’t get depleted, or doesn’t deplete very much. That doesn’t mean that willpower never gives out- clearly it does. It simply means that doesn’t necessarily have to get weaker with exertion. Your willpower can be as strong in the afternoon as it is in the morning.

That brings up another set of questions: to what extent can willpower be improved with practice, and how can you improve it? And do some people just have inherently better self-control than others?

Self-control: Not starting is better than stopping

A common platitude states that willpower is like a muscle: it gets stronger when you use it. Leaving aside the fact that this isn’t quite how muscles work- they get stronger when recovering from exercise- the evidence for the trainability of self-control is mixed.

In one study, subjects who underwent a self-control training session prior to performing an ego depletion task showed no greater self-control than subjects who had not taken part in the training session.8 This suggests that self-control can’t be significantly improved in a single training session, but what about improvement with long-term practice?

The evidence is mixed. One study found that two weeks doing any of three different self-control exercises lead to improved self-regulatory ability.9 Another study found that six weeks of self-control training did not improve participants’ self-control.10 A third study found that self-control training did produce measurable improvements in exercise performance, even when the training exercises utilized non-physical tasks.11

Why the discrepancy in the results? Other than sheer chance and the aforementioned publication bias, one meta-analysis found that it depended on the type of self-control task the subjects had to complete. Significant training improvements were found for go/no-go tasks, but not for stop-signal tasks.12 Another study on children 7-12 years old found that stop-signal tasks were more difficult than go/no-go tasks.13

In plain English: people got better at not giving into temptation in the first place, but they didn’t show much improvement at stopping a bad habit once they had started. Not only is it easier to not start eating a donut than to stop eating one halfway through, but people also have more capacity to improve their “don’t eat the donut” skill.

There is a big question as to whether the self-control tasks used in these studies truly have any carryover into real-world challenges. With that in mind, one last study bears mention. Researchers McKee and Ntoumanis trained 55 obese subjects in six self-regulatory skills: Delayed gratification, thought control, goal setting, self-monitoring, mindfulness, and coping. They found that this training produced significant body fat loss, as well as improvements in self-efficacy and body image, as measured during a follow-up four weeks after the end of the intervention.14

This study is notable because it measured its effect via an outcome with real-world importance- fat loss. It differed from other studies in that subjects were trained in six different skills rather than just one. This method of working on several skills at once may produce superior results because small improvements in several areas are better than a big improvement in one area- or because the odds are that if you work on six different methods of self-control, at least one is likely to work for you.

Resisting vs avoiding temptation

This leads us to another question: are people with high self-control really better at avoiding temptation, or do they feel less temptation in the first place?

A series of three studies in Germany found that individuals who scored high in (personality) trait self-control actually performed worse at tasks which tested their willpower via several different methods. The researchers conclude that people with high trait self-control engage in less frequent impulse inhibition in their daily routines. In other words, they’re not better at resisting temptation, but they experience temptation less often.15 Unfortunately, the researchers did not answer the question of whether such individuals simply don’t feel tempted by the things that tempt others, or whether they structure their daily routines so as to avoid temptation.

On the other hand, another study by American and Dutch researchers- this time specifically on dieting- found that successful dieters are no less tempted by unhealthy foods than anyone else, but are more likely to attempt to resist the urge to break their diets.16 Why the difference from those other studies? It could be that junk food is so ubiquitous that it can’t be completely avoided, forcing dieters to get good at resisting temptation. It could also be that the German studies defined trait-self control in a way that bears little relation to real-life discipline.

So how do you feel less tempted to break your diet, or skip workouts? A recent series of studies by several teams of Canadian researchers suggest that it depends on where your motivation comes from. They found that people who are motivated by the feeling that they “have to” reach a goal engage in more effortful self-control, while people who “want to” reach their goal experience fewer goal-disrupting temptations and thus don’t need to exert as much self-control.17 It seems the old cliche that you just have to want it badly enough has some truth to it after all.

As defined by the study, “want-to” and “have-to” motivation roughly correspond with intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, which is another

Motivation: The utility of extrinsic incentives and cognitive dissonance

You’re probably somewhat familiar with intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, and odds are you’ve heard the following: intrinsic motivation comes from within, while extrinsic motivation comes from without. Intrinsic motivation is better because it is self-sustaining. Extrinsic motivation can produce short-term results, but it’s bad because it undermines intrinsic motivation, so it backfires in the long run.

That’s the pop-psych view of motivation. And it is accurate…in some cases. But as is often the case, the reality is a bit more complex. One literature review found that undermining effects were well-supported in economic research, but not in health research.18 The authors attribute this partly to the fact that most health studies use subjects who initially have low levels of motivation for health-related behavior; they found that extrinsic incentives are more likely to reduce intrinsic motivation when intrinsic motivation is high to begin with.

A 2016 experiment found that obese women on a behavioral weight loss program lost significantly more weight when the program was paired with small financial incentives. Moreover, members of the experimental group showed significantly higher extrinsic and intrinsic motivation compared to women who were not given financial incentives. However, weight regain during the post-study period was not significantly different between the two groups.19

These two studies suggest that extrinsic incentives are likely to be more helpful for novice trainees, particularly obese ones, but less effective- possible counterproductive- for intermediate and advanced trainees. However, it’s important to remember that most studies use financial incentives, and non-financial incentives may have different effects. It’s possible that if the offered incentive is something directly related to fitness- such as new gym gear or cooking tools- it might very well support intrinsic motivation by inducing cognitive dissonance. Unfortunately this hasn’t been tested in a lab setting yet, but it is a ripe area for future study.

Another study did find that cognitive dissonance could be used to enhance intrinsic motivation. Husted and Ogden found that reminding bariatric surgery patients how much they had invested in weight loss by getting bariatric surgery caused them to report significantly less enjoyment of high-calorie foods and less desire to eat said foods. More importantly, they lost 6.77 kg in the three months after this intervention, compared to just .91 kg for a control group.20 Reminding people of the effort they’ve already made to get into shape appears to be very effective.

One meta-analysis of motivational studies (not all of them health-related) found that while tangible incentives often reduce intrinsic motivation, verbal praise tends to increase it.21 This may be a cognitive dissonance effect- praise feels good but has no tangible value. On the other hand, it could very well be mediated by changes in the recipient’s self image. That is, being praised for doing X causes the recipient to view themselves as someone who does X.

Self-efficacy is of secondary importance

One oft-suggested approach to fat loss is to improve patients’ self-efficacy- that is, their confidence in their own ability to reach their goals. High self-efficacy is correlated with good health, fitness, and success in pretty much all areas of life. Of course, correlation is one thing, but does self-efficacy directly cause people to get into better shape?

A clinical trial by Burke et al found that including self-efficacy training in a behavioral weight loss program increased the amount of weight lost during the treatment period. More importantly, the group that received self-efficacy training did not experience significant weight regain after the treatment period, while the group that didn’t receive self-efficacy training did regain weight during the 6-month follow-up period.22

A 2012 meta-analysis of behavioral change studies identified 19 behavioral change techniques (BCTs) that were associated with positive changes in physical activity, 2 BCTs associated with improvements in both physical activity and self-efficacy, and 2 BCTs associated with self-efficacy but not physical activity. In all, out of the 61 comparisons they identified in which obese adults experienced improved self-efficacy towards engaging in physical activity, only in 42 of those did the subjects actually engage in more physical activity. 23 (Note: most of the studies reviewed included used more than one BCT simultaneously)

All in all, the study found that most behavioral weight loss techniques increased physical activity without having a discernible effect on self-efficacy, and the authors concluded that mechanisms other than self-efficacy may be more important for promoting weight loss, at least in obese adults.

Why such a weak relationship between believing in yourself and being successful? Two other studies suggest two possible answers. A 2013 study published in the Journal of Health Communications found that weight loss messaging that targeted subjects’ self-efficacy did indeed increase subjects’ feelings of self-efficacy, but not their beliefs in the importance of body weight management. Messaging that did not target self-efficacy did not increase subjects’ self-efficacy, but did increase their beliefs in the importance of body weight management.24 Self-efficacy could mean a few things; researchers usually assume it will mean believing “I can lose weight,” but it could also mean “I can live just fine without losing weight.”

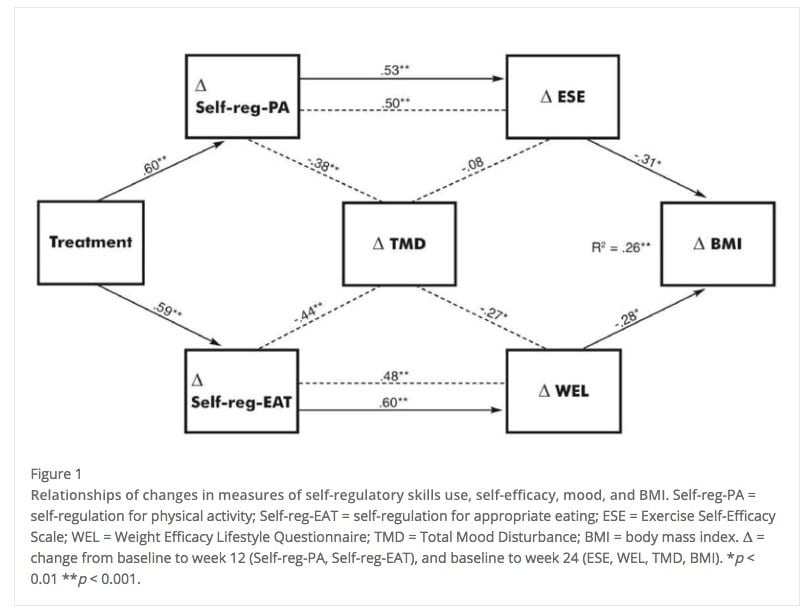

A separate study by Annesi and Gorjala assessed the impact of a program that emphasized nutrition, exercise and self-regulatory skills, but not self-efficacy. They found that the program significantly increased participants’ sense of self-efficacy, and that 26% of the change in BMI experienced by participants was explained by changes in self-efficacy. They found the relationship between self-regulation and self-efficacy to be partly mediated by mood- that is, subjects believed in themselves more when they were in a good mood.25

From Annesi and Gorjala (25) Shows the relationships between the treatment program, self-regulation, mood, self-efficacy, and BMI reduction.

As you may recall, the Mkee and Ntoumanis study (14) also found that a program that taught self-regulatory behaviors also had a secondary effect of improving self-efficacy. It seems, then, that self-efficacy is important, but secondary. The chain of effects here seems to be engage in better health behaviors > get into better shape > feel happy > feel more confident in your abilities > engage in even better health behaviors > get into even better shape. Being confident and believing in yourself is great, but it comes from actually getting good at what you’re doing.

One last thing to take note of is that virtual all studies on self-efficacy and fitness are performed on obese individuals. So what about those of us who are in pretty good shape already? For the most part, people who are in good shape already have high perceived self-efficacy regarding diet and exercise. It’s also worth considering that once you’re serious about fitness, excessive confidence could actually lead to overtraining or overly aggressive dieting. While this warrants more research, there’s currently no reason to believe that a self-efficacy approach is any more effective for non-obese individuals than obese individuals.

Keep stress to a minimum

It’s well-known that high levels of psychological stress lead to impaired decision-making. As Menno has previously explained, stress can also cause excess abdominal fat storage via elevated cortisol levels. So what does the literature say about stress management as an approach to fat loss?

Two recent studies demonstrated the effectiveness of stress management training in obese Greek26 and African American27 women. The Greek study noted higher restrained eating compared to a control group, while the American study found that stress management training produced a decrease in salivary cortisol levels. The subjects in the American study were taught behavioral weight management techniques simultaneous with the stress management training. The Greek subjects were not, but since they were recruited from an outpatient weight loss clinic, one can speculate that they most likely were receiving weight loss advice from their doctors at the time of the study.

A systematic review of 14 studies in which mindfulness meditation was used as the primary intervention for weight loss found that mindfulness meditation was effective at decreasing emotional eating and binge eating in people who are prone to those issues. It found mixed evidence for effects on weight.28

Bear in mind that mindfulness was the primary intervention in the studies examined by this review, whereas in the other two studies it was applied secondarily to weight loss behavioral change training. The lesson here seems to be that stress reduction/management can be very helpful, provided that a) you know that stress is a major issue contributing to poor diet or lack of exercise, b) you work on behavioral change at the same time, and c) you’re following a good fitness program in the first place.

A different meta-analysis on the effects of stress on physical exercise found that stress generally impairs efforts to be physically active. Most people get less exercise when they’re stressed. However, they noted that ten out of fifty-five reviewed studies found evidence that their subjects exercised more when stressed out. The authors of the meta-analysis note that this seems to confirm that some individuals use exercise to cope with stress.29 That offers one further avenue for dealing with stress: employing a bit of psychological jujitsu, you can use stress as a positive motivator by finding healthy foods or forms of exercise that you find to be enjoyable or relaxing. Rather than exercising in spite of stress, you can exercise because of it.

People are the product of their environments

Sociologists, social psychologists and urban planners have long known that our behaviors and attitudes are heavily influenced by the people in our lives and the places we live and work. Numerous studies bear out the effect of our environment on health behaviors.

One American research team found that among adolescents in New Haven, Connecticut, (if you’re not familiar with New Haven, let’s just say it’s a town you drive through with your windows up and your doors locked) neighborhood characteristics had a major impact on health behaviors. Students who lived within a 5-minute walk of a grocery store ate healthier food and had lower BMIs on average, while students who lived within a 5-minute walk of one or more fast food outlets had higher BMIs and ate more junk food. Strong social ties were associated with lower BMI, while higher property crime rates in the neighborhood were associated with higher BMI. Having easy access to parks, playgrounds and gyms was associated not only with getting more exercise, but also with healthier eating behaviors.30 One drawback to the study: it did not control for socioeconomic status.

An experiment on Dutch high school students found that students who were told to eat more fruit actually ate significantly less fruit than the control group. However, students who were told that other students eat a lot of fruit ate significantly more fruit than both the control group and the group who were told to eat fruit. Interestingly, the group who were told that other students eat fruit did not express greater intentions of eating fruit; they conformed to perceived social norms without having any conscious intention of doing so.31

That’s cool, but what about adults? A study of thousands of participants in online weight management communities found that, of users who had at least one friend in the network, 96% remained active in the program for long periods of time- over half a year on average. They found a direct correlation between the number of friends a person had in the weight loss community and how much weight they lost. In fact, social connectivity within the weight loss community was the biggest predictor of weight loss- more so than either initial BM or adherence to self-monitoring habits.32

Okay, but how about non-obese adults? Another study of users (of all body types) of a mobile exercise gamification app found, once again, that the more friends they had using the app, the more they exercised.33 Users reported being motivated by social recognition, or as the authors put it, “Working out for likes.”

Two more studies demonstrate the effectiveness of modifying one’s environment. A survey of 1660 English primary care patients asked people what barriers made change difficult for them. Barriers were classified as either internal- such as being busy or lazy- or external, such as not having access to a gym. Participants who identified external barriers were more likely than those who focused on internal barriers to start exercising more.34 Another study comparing the results of two weight loss programs found that a program emphasizing environmental modification and habit change produced similar initial results compared to one focusing on self-image and one’s relationship with food. However, the program that focused on habits and environmental factors proved far more effective at prevent rebound weight gain.35

The sum total of the data indicates that you will be healthier if you live in a physical environment where healthy behavior is convenient and unhealthy behavior is not, and a social environment in which healthy behavior is both encouraged and socially rewarded. It also refutes the common belief that citing external reasons for failure is just “making excuses.” In fact, blaming external factors for your failures is great, as long as you then fix those factors.

The Instagram effect, or why food porn is good for you

If you’re a college student, you might find this hard to believe, but back in my day people didn’t take pictures of everything they ate and post them on the internet. In fact, I’m pretty sure that back then “food porn” referred to actual porn involving food.

But now it’s not a meal unless you have your camera out, and 32-year-old geezers like me are asking: is all this instant-gramming and chat-snapping healthy? As it turns out, that depends.

Yep, pretty much like that.

A series of studies which tested the impact of photographing food before eating it found that for pleasurable or “indulgent” foods, snapping a photo before did increase subjects’ enjoyment of the food and their evaluations of its taste. For healthy foods that are less inherently pleasurable, this effect was observed only when social norms around healthy eating were made salient, i.e. when subjects were reminded that other people eat a healthy diet.36

Viewing food porn is also pleasurable- as if you didn’t know that. A pair of studies published in 2013 found that viewing photographs of food has an effect similar to actually eating food. Crucially, the pleasure from viewing food photos did not induce subjects to want to eat the food in the photos. Quite the opposite- viewing the photos induced satiety, decreasing the desire for and enjoyment of foods of the type shown in the photos.37

It turns out millenials may be onto something. The Instagram effect is both very real and very useful. Taking photos of your food is an easy way to increase enjoyment, so start taking photos of your healthy meals, but not your cheat meals. As for viewing food porn, the evidence is rather counterintuitive: it’s pleasurable, but since it reduces desire for the food you’re looking at, you should only browse Instagram photos of unhealthy foods. Well, for entertainment at least- don’t let this stop you from looking up healthy recipes online.

There is one piece of bad new: a separate 2017 study from the John Fawkes Journal of Broscience and Social Criticism found that Instagramming everything you eat is still totally obnoxious. (citation needed)

Practice remembered enjoyment

If you remember that you enjoyed something the last time you did it, you’re more likely to do it again. I’m not going to cite a study for that; you’ll just have to trust me. As it turns out, you can make enjoyable experiences more memorable simply by dwelling on them for a few moments right after they happen.

A study by Robinson et al demonstrated that remembered enjoyment of food could be increased by instructing subjects to rehearse what they enjoyed about the food immediately after eating it. A follow-up study then showed that this increase in remembered enjoyment significantly increased the amount of that same food that subjects consumed when it was offered as part of a buffet lunch the next day.38

This has clear implications for dietary compliance; by taking a moment after eating a healthy meal to think about what you liked about it, you’re more likely to eat healthy food in the future. This would presumably combine well with the Instagram effect- photographing your food before eating it makes it more enjoyable, then thinking about the meal for a few moments afterward makes the enjoyment more memorable, and that remembered enjoyment can be heightened further by reviewing the photo.

One can imagine other applications of this technique. Perhaps you could practice remembered enjoyment after physical activity to make yourself more likely to exercise in the future. Perhaps after a cheat meal, you could pause to reflect on what you didn’t like about it. For the time being however, both of those ideas remain unstudied and purely theoretical.

Use smaller plates to eat less? Maybe

One common piece of diet wisdom holds that people should eat off of smaller plates, because size-contrast illusions cause use to underestimate how much we eat when the plate is big, and overestimate- or at least accurately estimate- caloric intake when eating off a small plate. However, the evidence for this is mixed.

DiSantis et al found that this was indeed the case when elementary school-aged children were allowed to serve themselves using either child or adult-sized plates. They both ate and wasted significantly more food when using the adult-sized plates.39 On the other hand, in a study in which college students were asked to estimate the volume of a portion of spaghetti, the size of the plate that the food was presented on made no difference.40

What made the difference? The obvious answer is that the first study used children and the second used adults. Yet adults are perfectly capable of mindless eating. An equally plausible explanation is that the children in the first study were not instructed to pay attention to what they ate, while the adults in the second study were specifically tasked with estimating how much food they were looking at. It’s possible that larger plates only make people eat more when they’re not paying attention.

A literature review by Libotte et al found that the effect of plate size on energy intake was highly inconsistent and depended on the environment, type of food, type of serving container, and whether the meal was self-served or served by someone else. A follow-on experiment by the same team found that when serving themselves at a buffet, plate size did not have a significant impact on calorie consumption. However, people with larger plates ate more vegetables, particularly vegetables served as side dishes.41 A very interesting result indeed, but it’s contingent on the meal including vegetable side dishes- remember that the college student study used spaghetti.

The sum total of experimental evidence suggests that using smaller plates causes people to eat less only when they are serving themselves and not paying attention to how much they eat. It does not seem to make a difference when you’re not serving out your own food, so don’t be a dick and demand that your waiter serve your food on a small dish.

However, the ways in which plate size interact with other factors severely limit the usefulness of this approach. If you’re mindful of what and how much you’re eating- which you should be most or all of the time- plate size seems to make no difference. And if you’re eating healthy food with lots of vegetables, which again you should be 90% of the time, using smaller plates actually seems to be counterproductive, as it’s the veggies that lose out. This is particularly true when the vegetables are a side dish, meaning they’re separable from the calorically dense components of the meal.

In short, using small plates may be helpful for total beginners to dieting who haven’t yet built the habits of eating vegetables with every meal and being mindful of what they eat. For people who are at least somewhat successful at eating healthy food, it’s probably good advice for cheat meals, but counterproductive the rest of the time.

Key takeaways and action steps

Alright that was a lot to cover. You can take a deep breath and relax- I’m done quoting science at you. Based on the sum total of the research to date, here are some things you can do to improve compliance with your diet and your fitness program:

- Practice mindfulness, particularly when eating. Take the time to savor every bite. If you’re not counting calories, at least take a close look at your food before eating and try to get an accurate estimate of how much food it is.

- Take photos of your food before eating, particularly healthy food.

- When you get a craving for junk food, you may be able to satisfy that craving by merely looking at pictures of the food you crave. This may not work for everyone- take a week or two to experiment with it.

- Look for ways to modify your environment to make healthy behaviors more convenient, and unhealthy behaviors less convenient. Live somewhere walkable, with a gym and grocery store nearby. Don’t keep cheat foods at home. Keep your kitchen clean.

- After eating a meal that fits your diet, take a few moments to think over how much you enjoyed it and what you liked about it. Do the same after working out- think about how good you feel for having done your workout.

- When you feel stressed out, relieve stress by doing a few minutes of bodyweight exercise and eating a healthy, low-calorie snack- not by breaking your diet.

- Join and/or spend more time in a social environment where healthy behaviors and encouraged and praised. Use a mobile fitness app that has social features. Get as many of your friends as possible to join it with you.

- If you have a cheat meal, eat off a small plate if possible. When eating healthy food with vegetables, favor larger plates. However, once you’ve gotten good at eating mindfully, this plate stuff probably doesn’t matter.

- Don’t struggle against temptation if you can ignore it, and don’t ignore it if you can avoid it altogether.

- Do everything you can to eliminate sources of stress in your life. If you feel that stress is a major problem for you, take a stress management class.

- Use psychological momentum to your advantage. It’s easier to not start eating junk food than to stop once you’ve started. If it’s hard to motivate yourself to work out, just make yourself go to the gym and step into the weight room- once you’re in motion, it’s easier to keep going and do your workout.

- If you are a total novice and very unmotivated overall, use small tangible incentives to motivate yourself, such as giving a friend $5 every time you cheat on your diet, or buying yourself new gym pants if you do all your workouts for a month. If you’re intermediate to advanced, focus more on getting intangible incentives like praise from your social group.

- Don’t try to feel more confident or boost your self-esteem. Just follow the program, get strong, lose fat and gain muscle, and confidence will follow.

- Start viewing your willpower as an unlimited resource that doesn’t deplete with use. It’s a brick wall, not a gas tank.

That’s a lot of things for you to do, and nobody should ever try to do all of that at once. Instead, pick 2-3 things from that list that seem most relevant to you and spend 2-3 weeks working on them until they become habitual. Once you’ve done that, pick a couple more items from the list.

And that’s how mere mortals like you and I can use the power of science to make program adherence a piece of (low-carb) cake.

Author Bio

John Fawkes is an American fitness coach who uses evidence-based methods to help people gain muscle and lose fat at the same time. He is a current Henselmans PT student. John’s main specialties are sports psychology, fitness for travellers, program individualization, and dealing with fatigue and sleep issues.

Website: johnfawkes.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/JohnFawkesBlog

Want more content like this?

Want more content like this?

Then get our free mini-course on muscle building, fat loss and strength.

By filling in your details you consent with our privacy policy and the way we handle your personal data.