Study review: More volume, more gains?

This is a guest post by Calvin Huynh. He covers a messy but very interesting new study on low vs. high training volumes in detail.

You thought the volume debates were over? Well science is constantly revealing more and whether evidence-based is still considered cool, we are all held accountable to existing data. A new interesting study adds another piece to the volume puzzle.

Dellatolla et al. took 11 trained men who had ~6 years of lifting experience. They were also required to squat at least 1.5x bodyweight and deadlift at least 1.75x bodyweight.

Only 9 men completed the study and over double the sample size was originally planned, but COVID-19 threw a wrench in that, as we know it does. We’ll take what we got though, as there are many strengths to this study.

Caloric intake was relatively matched. I say relatively because they had frequent check-ins during which all subjects were advised to eat at maintenance or a surplus. Any deficit was compensated for with more calorically-dense food to maximize anabolism.

3RM testing was done and body composition was measured via DEXA, Bod Pod and ultrasound.

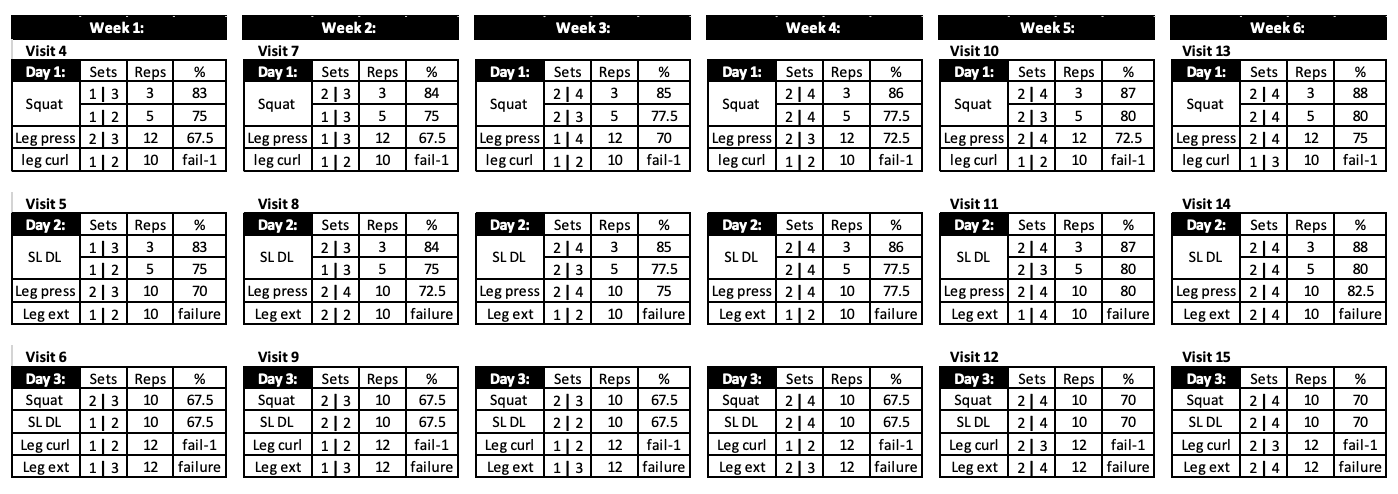

Subjects were split between a high-volume (HV) and low-volume (LV) group. The authors counted volume as working sets per lower body exercise, but because hypertrophy is largely a local process, I’ve split up the working sets into quads and hamstrings separately.

- Low volume group: Progressed from 5 to 9 sets of hamstrings and from 10 to 14 sets of quads across 6 weeks.

- High volume group: Progressed from 11 to 18 sets of hamstrings and from 19 to 28 sets of quads across 6 weeks.

Volume wasn’t constant but increased over the course of the weeks which can be a bit of a confounder. It could be too low/high for the individual, but we can still compare doing less vs doing more sets between groups.

Progressive overload was implemented in both groups with a combination of sets shy of failure and to failure. Earlier sets within the workout had 1RM% that increased over the weeks. The later sets were either taken 1 rep shy of or to failure.

Participants also trained in a variety of rep ranges.

In addition, proper rest periods (3-5) and optimal frequency distribution was implemented, which is somewhat rare in a volume study.

Furthermore, past studies may have also masked the benefits of higher training volumes by not distributing sets throughout the week properly. If you do too much volume within one session, you may overshoot the per session volume limit.

However, this study accounted for these variables, so kudos to the authors.

Oh and before I forget, there was also some mental training done in this study, but it’s honestly quite irrelevant.

So What Happened?

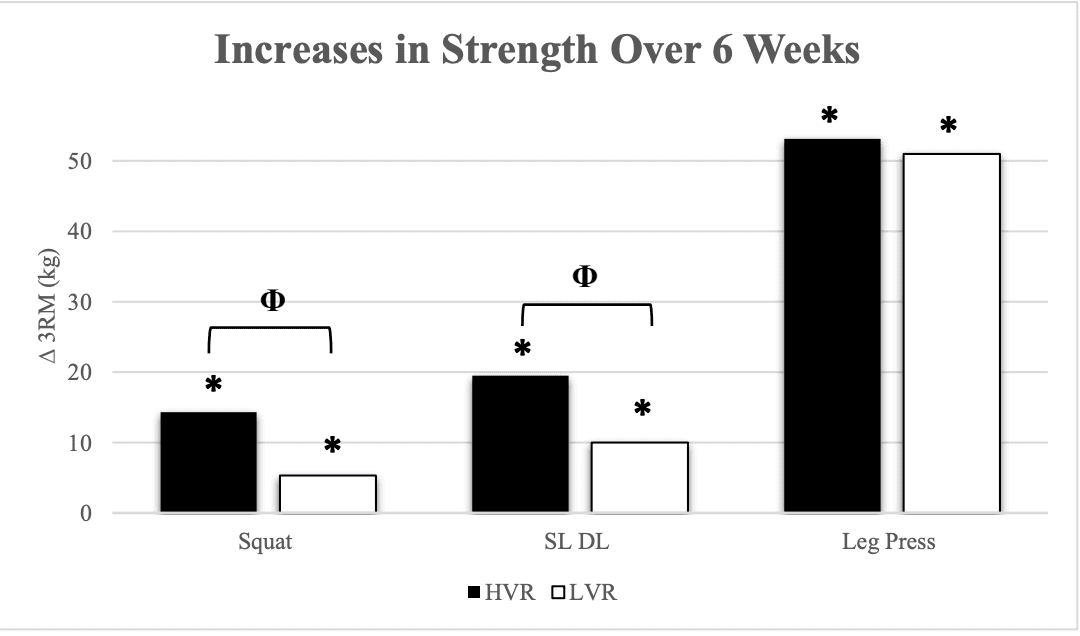

After 6 weeks of 18 brutal leg days, the high-volume group gained more muscle and strength based on all measuring methods. The high-volume group gained double the squat and stiff-legged deadlift strength, but leg press strength gains were similar. This may be due to free-weight movements being more technical, so performing more volume allows for further practice.

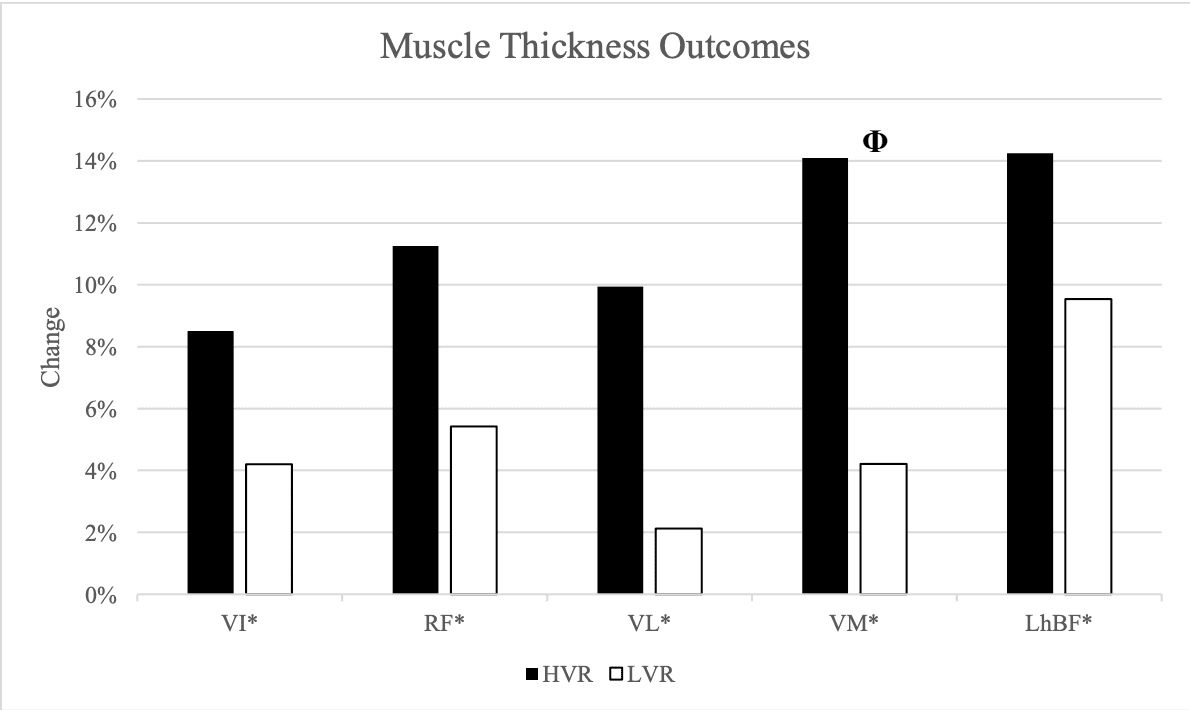

The high-volume group also gained significantly more muscle based on every measure.

Takeaways

HIT style low volume defenders often advocate for pushing for more intensity by sacrificing volume. This can be useful if you’re short on time, but it won’t cut it if you’re looking to maximize hypertrophy. In this study design, the low volume group actually performed more reps per set on average, especially in the failure sets, because they had accumulated less neuromuscular fatigue prior to the failure sets, yet the low volume group still didn’t grow as much. People often forget it’s not only about how much work you can do in 1 or 2 given sets. It’s about maximizing your performance across all sets within the session and across the week.

The small sample size is a limitation of this study, but to be fair, the high-volume group started with more strength and muscle, so they were closer to their genetic ceiling. In theory, they should’ve therefore been disadvantaged. The extra volume had to make the difference. When you implement proper rest periods, distribute your volume accordingly, vary your rep ranges, and don’t train exclusively to failure, you’re able to apply a higher dose (volume) of stimulus.

Thus, the short answer to the never-ending volume question is, you should do more, if you can recover from it. The caveat is you have to understand how to manage other variables to let volume shine. If you’re an advanced lifter, you may tolerate more than you think. A short period of high-volume, high-frequency training is worth experimenting with.

Study Reference

Dellatolla, Jason. “The Effects of High- vs Low-Volume Resistance Training Combined with Critical Reflection on Muscular Hypertrophy and Strength.” TSpace, 1 Nov. 2020, tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/103703.

Want more content like this?

Want more content like this?

Then get our free mini-course on muscle building, fat loss and strength.

By filling in your details you consent with our privacy policy and the way we handle your personal data.